For years, a 12-step program laid out in just 200 words has held a virtual monopoly on the treatment of alcoholism. Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) is famous, infamous, global and highly influential, and it's based on giving up booze, completely.

For most people seeking help with alcoholism, abstinence is the only option. That view "is heroic and dangerous, and it doesn't do anything," Wim van den Brink, a spirited Dutch psychiatrist with a flop of white hair and glasses, recently told an audience of researchers in Vancouver, British Columbia. Even in the city that is home to North America's only supervised safe-injection site for heroin addicts, van den Brink's proposal represents a radical departure: He wants to help alcoholics go on drinking, without all the problems.

The key, says van den Brink, who co-founded the Amsterdam Institute for Addiction Research, is a pill to curb drinking. The drug, nalmefene, acts as an alcohol antagonist; it binds to opiate receptors in the brain and reduces the rush of pleasure associated with alcohol. (It has also been tested, with less success, to treat compulsive gambling.) In one double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, sponsored by Lundbeck A/S, a Danish pharmaceutical company that manufacturers nalmafene, van den Brink and his colleagues studied 604 people who took the drug.

"We say, 'Just take the medication in case you go drinking,'" he says. "'Actually, you can even take it the moment you start the first drink.' This brings some of the responsibility back to the person."

Over six months, they found that those taking the drug reduced the number of heavy drinking days from 19 to eight per month, and effectively cut overall drinking by two-thirds. Van den Brink admits there was also a profound reduction in consumption in the placebo group, which nearly halved daily drinking—but the effects were amplified with the nalmefene tablet, to the equivalent of drinking a large glass of wine instead of an entire bottle. Two later studies, published in European Neuropsychopharmacology and Journal of Psychopharmacology, had similar results.

The drug, sold as Selincro, is available in Europe. In August, a clinical trial began enrolling patients for a U.S. study. If successful, it could have an enormous impact on public health. Alcohol is one of the most dangerous drugs in the world—some might argue it tops the list—and yet data show a massive treatment gap when it comes to alcoholism. An estimated 17 million Americans have an alcohol-use disorder; nearly 4 million have a dependence, and yet only 1 million are in treatment. At most, 300,000 take medication.

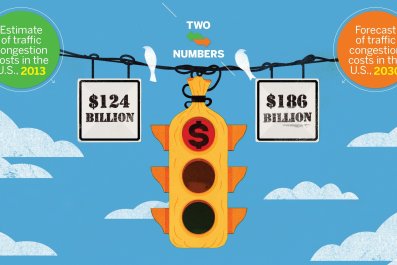

There are many compelling reasons to increase treatment rates: Immoderate drinking contributes to increased risk of liver disease, cancer and chronic inflammation. A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report, released earlier this year, states, "Excessive alcohol use is the fourth leading preventable cause of death in the United States and costs $223.5 billion, or about $1.90 per drink, in 2006." Other studies measuring harm have ranked alcohol as more dangerous than cannabis, cocaine and heroin.

AA generally frowns on the use of prescription drugs because they "threaten the achievement and maintenance of sobriety." The program does work for some, but, despite its prominent role in culture and its prevalent use in court-mandated rehabilitation, it's not for everyone. In fact, the vast majority of people who enroll in the AA program fail to stick with it. In 2006, a review of alcohol treatment studies by the Cochrane Library concluded, "No experimental studies unequivocally demonstrated the effectiveness of AA or [twelve-step facilitation] approaches for reducing alcohol dependence or problems." In The Sober Truth, a book published in 2014, Dr. Lance Dodes and his son Zachary Dodes reviewed the literature and concluded that AA's overall success rate was only 5 to 8 percent.

Van den Brink strongly believes that reduced drinking is a viable treatment goal for alcohol-use disorders. If addicts who have 100 drinks per week can cut that down to 25, he says, they may regain control of their lives. There's some precedent: Harm-reduction public health policies, which focus on diminishing rather than eliminating the harmful consequences of certain behaviors, have been shown to be effective in treating heroin addicts, for example.

Todd Nease, 38, of Davis, California, says he has been in and out of AA for about 18 years and, at times, left the program drinking more heavily than before he attended meetings. His doctor pushed him to consider total abstinence. Eventually, he found a harm-reduction support group called HAMS and cut back to once a week. "I prefer drinking when I can control it," he said. "I'm not big on medications, but if it was for temporary use, I don't see why not."

A treatment that reduces drinking offers those who don't feel they can or don't want to go abstinent another option. Robert Swift, a professor of psychiatry at Brown University, believes abstinence is usually the best option to treat alcoholism, but said, "One size does not fit all. So there may be people who really cannot drink even one drink, and then there are people who can go back to social drinking."

For instance, Swift regularly treated a patient who has trouble staying abstinent between Thanksgiving and New Year's with disulfiram (an older drug, sold under the brand name Antabuse, that causes an unpleasant reaction to alcohol consumption). "He comes in to take medication just those three months," he said. "That's the targeted approach. The rest of the year he's fine, but there's just too much alcohol around during the holidays."

Nalmefene is part of a small but growing number of pharmaceutical options. For instance, a review paper published in The Journal of the American Medical Association earlier this year by Daniel E. Jonas, a researcher at University of North Carolina, highlighted the effectiveness of drug interventions. Two other opiate antagonists, naltrexone (ReVia) and acamprosate (Campral), have been approved since 2006. These medications tend to be underused, and when they are used, it's to maintain abstinence or prevent relapse to heavy drinking.

Nalmefene (Selincro) is the first drug approved anywhere for the reduction of alcohol consumption. It's also taken "as needed," so it puts the patient in control. Nonetheless, Jonas says, such medications still face long-standing skepticism; primary care doctors can be reluctant to prescribe them—either because they're not aware of the drugs, they're not comfortable prescribing them or they've been taught to refer patients to specialists (who aren't available in many areas of the country).

Critics contend the latest research on nalmefene found that only modest, incremental decreases in heavy drinking days—and that there are much better ways to end problematic drinking. In a recent op-ed published in The BMJ, Dr. Des Spence, a general practitioner in Scotland, argued that the drugs are little more than a commercial venture that distracts from efforts to limit the availability of alcohol.

Nevertheless, for those seeking help, a non-habit-forming drug may be one step toward moderation—even if it does not work for everyone. Alan Surratt recently participated in a pilot study through the University of Washington (which was published in the journal Substance Abuse) to treat the homeless with injections of naltrexone (Vivitrol). His problem, he says, had been binge drinking.

"I might be dry for three weeks or so and then go on a bender until the money ran out. That would be only reason I would stop," he says. He adds that "AA's big thing is it would be a miracle for an alcoholic to drink like a normal person. On the medication, I found that I was drinking normally. I didn't have a desire to get polluted or blown away."

He feels, Surratt says, like a normal person again.