- India

- International

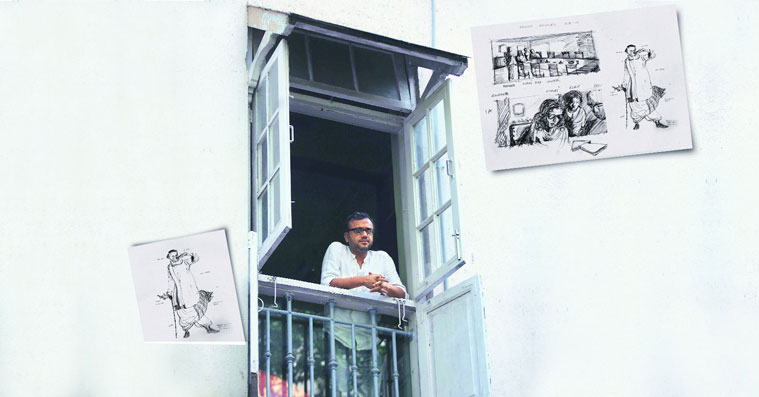

Dibakar Banerjee on How to find a movie

In cinema, a character is often confused with a role.

One of my ongoing quests is to get inside the head of a woman. It started with LSD. The idea was to show sex without titillating the audience in the least bit, but repelling them.

One of my ongoing quests is to get inside the head of a woman. It started with LSD. The idea was to show sex without titillating the audience in the least bit, but repelling them.

By Dibakar Banerjee

Through his craft, a filmmaker looks for many things — a character, a few moments of magic, and, sometimes, the film itself. Dibakar Banerjee talks about the many quests that lead to his cinema.

At the core of any film are its characters. But what you or others perceive as a character can be very different from what I see as one. Is it the physicality? Is it what the person does, what the person says? Or is it what the person conceals? Or is it what that person wants to be perceived as?

In cinema, a character is often confused with a role. In Love Sex Aur Dhokha (LSD), there’s a scene in the first story, where the girl’s father says, “Bachpan mein maine bhi bahut role kiye hain: army, navy, driver…” He thinks of characters as the uniform they wear.

But for a deeper understanding of a character, we need to look at ourselves. Often, a character is what you conceal, what you are trying to project. The difference between what you are trying to project and what you are is the fuzzy zone that defines a character — the difference between the external and the internal. How a person will lie or conceal (something) reveals a character. In Detective Byomkesh Bakshy!, a client assigns Byomkesh a case, but he conceals a few crucial facts. The client wants the case solved, yet he doesn’t want it solved. This duality is his character.

Most of our art, fiction and narrative fiction comes from a conflict within a person. It forms every sentence and line the character says, it exemplifies the conflict of our existence. Take, for example, Vijay Chauhan or any of the other Angry Young Man characters. The man wants acceptance and love, but rejects it outwardly. The most loved character of Indian masses is the street-side goon with the golden heart, who cries for his mother, sister or lover. But when he comes out on the street, he projects a tough-guy facade and beats everyone up.

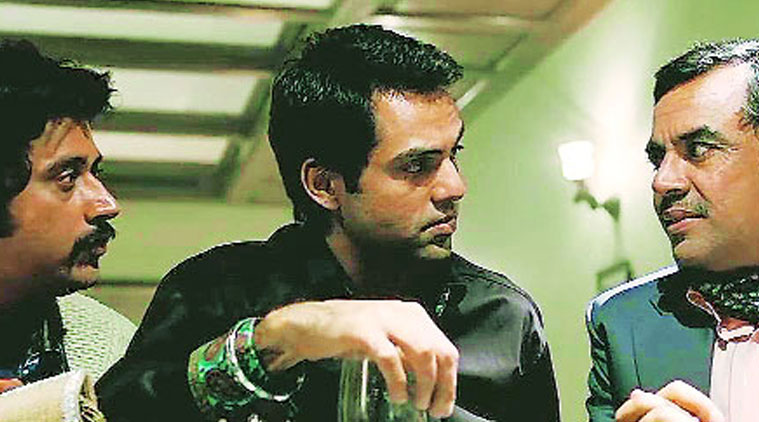

As a filmmaker, what I have learnt is to try and find these conflicts. The golden rule in writing a character: find the gap between what the character wants and what it needs. Byomkesh Bakshy wants to solve a case, what he needs is something else. What Lucky in Oye Lucky! Lucky Oye! wants is a washing machine, what he needs is an identity. What a character wants, he is consciously aware of. But what he needs, he doesn’t realise. So in the case of Jogi Parmar in Shanghai, what he wants is to go to bed with Kalki Koechlin’s character, what he needs is respect. I am not such a good writer and I’m not such a good judge of what I am doing, unless in retrospect. For me, most of my work is a series of mistakes or unfulfilled choices, somehow salvaged by technique and ruthless contempt for my own work. If I didn’t have the latter, I’d be a very bad filmmaker.

All the mistakes of my films are about forgetting the golden rule: when characters are not driven by that conflict, but act depending on the director or the writer’s external plot needs. But cinema finds its nirvana spot when the director or writer’s plot or subtext requirement merges seamlessly with a character’s own impulse — when you can’t tell one from the other.

Like the last shot of my short in Bombay Talkies. There is no need for me to go to the exterior of the chawl, take that wide shot. But if I don’t, I won’t be able to see Nawazuddin Siddiqui’s character throw his hands up in the air in excitement. In seeing him do so, and seeing the whole chawl through a wide angle shot, some magic happened — it’s a scene a lot of people told me they were moved by. But, of course, it’s by design. It’s an external device of the director to show that the character has broken out of the oppression and had a moment of epiphany. And it also fuses with the director’s need. It’s such moments of magic a filmmaker seeks.

In another instance, in Shanghai, one sees Kalki’s character beating up the man who killed her beloved professor. When she finds the perpetrator, she cannot take revenge or act lofty because both go against her character.

Instead, she hits the man with a peetal ki thali again and again, and finally breaks down. In that moment, the perpetrator suddenly starts confessing, which triggers Jogi’s realisation that there is a recording of the killing. So Kalki’s catharsis, that man’s confession and Jogi’s realisation that leads to the climax, all happen at the same time. No one will see all these joints, but they form a moment in the film.

In LSD, there is a line that comes at the right time. Just before the beheading of the couple in the honour killing story, the girl’s brother says, “Bhagwan ne sabke liye jagah banayi hai. Tujhe ghar mein ghusne kya diya, tu apni jagah bhool gaya?” That one line says everything about the caste system and also defines the brother’s character.

Characters are often rewritten from scratch. They begin as something else and end up completely different. That’s true for films too. It happens when the core changes, evolves. Khosla Ka Ghosla! started as a film on the generation gap — it was about the problems between a father and a son. It then became Jaideep Sahani (co-writer) and my apology to our families for escaping and wanting to break away from the past. Later, we designed a cop-out towards the end. We realised we needed to give the family the plot of land back. It wasn’t set up as irony but as a definite quest, we were giving the audience hope at the end. At the same time, it became — and very pleasantly so — the divide between a Nehruvian, socialist India and India, post 1991. It’s the contrast between Khurana and Khosla.

One of my ongoing quests is to get inside the head of a woman. It started with LSD. The idea was to show sex without titillating the audience in the least bit, but repelling them. I think I succeeded with that. In the second story, the two were having sex butt-naked but people were repelled. That happened because the audience had spent 30-40 minutes with them already, as opposed to viewing sex for instant gratification.

On similar lines, my next search is to show savagery in a way that it repels and doesn’t lead to gloating. What is bravery? It is often defined by how many or how savagely one has killed. It perhaps carries on from our past, a time when men out to hunt for a bison would be goaded by their ilk, helping them kill better. At that time, it was survival. But that primal instinct still exists in us, although the world has changed. Research into riots will reveal how killing more and killing savagely is rewarded. My aim now is to find a way in which I can show acts of savagery but in a way that the audience feels revolted.

Click for more updates and latest Bollywood news along with Entertainment updates. Also get latest news and top headlines from India and around the world at The Indian Express.

Photos

Apr 26: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05