- India

- International

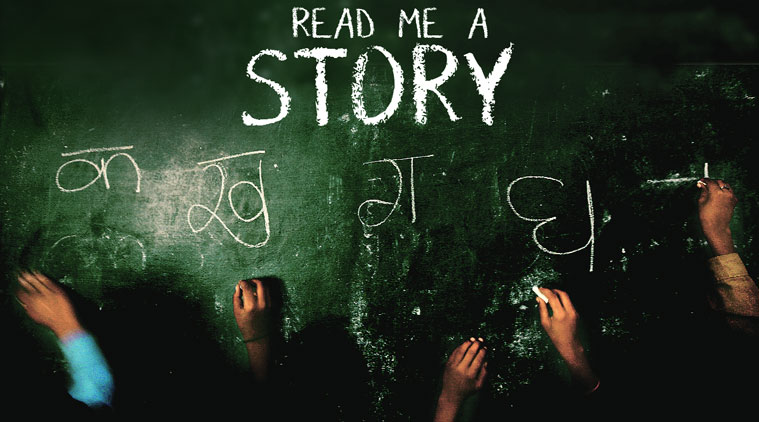

Big Picture: Read me a story

Year after year, Pratham’s Annual Survey of Education Report, or ASER, tells us about children who go to school but can’t read or do basic math.

Rampur district has some of the worst learning and dropout levels in the country; the primary school in the village has classes from I to V and only two teachers.

Rampur district has some of the worst learning and dropout levels in the country; the primary school in the village has classes from I to V and only two teachers.

Year after year, Pratham’s Annual Survey of Education Report, or ASER, tells us about children who go to school but can’t read or do basic math. This year, as ASER volunteers fan out across 570 rural districts, Uma Vishnu visits a village in Rampur, a district in UP with some of the worst learning levels in the country, to see what it is to read. Photographs: Praveen Khanna

Aao, padho.” Kusum, who had until then been stirring a cowdung slurry, looks up at the crowd of people who have just barged into her house. Read? No one had ever told her to do that. Not in school, where she sits in the back row of Class IX; definitely not at home. “My parents are away,” she protests, a thin brown film of the slurry coating her arms all the way up to the elbow. “That’s ok. Go wash your hands and try reading this,” goads Chandrika Prasad Maurya.

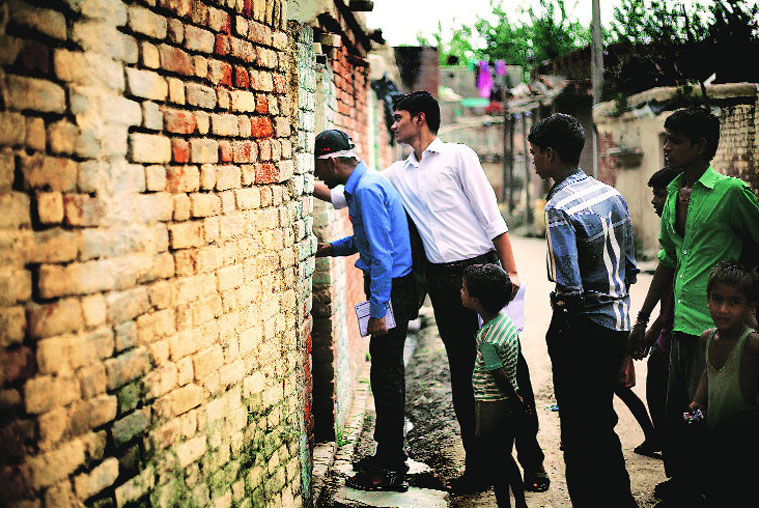

Maurya is with a team of volunteers that is conducting a household survey for NGO Pratham’s Annual Survey of Education Report or ASER, one of the most definitive barometers of learning levels among children between 3 and 16. This is the survey that has been telling us, year after year since 2005, that much of India can’t read and do basic math, that schooling is not the same as learning, and that the country needs to get its basics right.

This year, for the 10th year in a row, ASER volunteers have fanned out across 570 rural districts in the country. This village is among 30 in Uttar Pradesh’s Rampur district where volunteers will go to 20 households each, over two days, getting children to read.

So Kusum sits on the edge of a cot, the light from the skylight of the mud house falling onto the paper she is now holding, the water from her wet hands blotting the paper. She looks around her. The entire neighbourhood — children who were out playing, women, her brothers — has turned up to watch Kusum read. Her finger runs rapidly across the lines as she reads in a low, nervous drone: “Aaj Ravivar hai. Aaj chutti hai…” But that’s not what the text says. She should have been reading: “Raat ho gayi, chand dikh raha hai.” Kusum can’t read. Next, she tries reading words: paani, aag, taala. She can’t. Letters? She struggles, manages a few and then, gets up. She won’t read anymore.

“Okay, try some ghatai (subtraction),” says Maurya gently, handing her a pen and paper. It’s 41-13. She stares at the hyphenated pattern and finally writes 14 for 41. “What are you writing? It’s 41,” laughs a gangly boy standing next to her. Maurya shoos him away. After three attempts, she finally copies the numbers right, but can’t solve the problem. “Nahin kar payegi. She goes to school, but it’s no use,” says one of the women crowding around. Kusum shoots her a glare and the woman shoots back: “Galat kah rahin hoon?”

Kusum is 15, in Class IX, but can’t read a paragraph from a Class II textbook. Like 62.8 per cent of the children across the country who couldn’t last year, according to the 2013 ASER report.

Every year, the figures tell a story — of children who trudge to school, sit in crowded classrooms, spend hours staring at alphabets and numbers that swim against a blackboard, hear their stomachs growl at the smell of the mid-day meal wafting in from the school kitchen, wait endlessly for teachers to make an appearance and then, when the bell rings, walk back home. But can they read? Do basic math? Nobody asks them.

…

Rampur, which lies on the border with Uttarakhand, is the last of the plains of Uttar Pradesh. Once known for its formidable Rampuri chaku (knives), it now brandishes a somewhat less flattering record, regularly featuring on ASER’s report card as a district with some of the worst learning and dropout levels in Uttar Pradesh. The state itself ranks among the lowest in those parameters in the country.

Off the main Bilaspur road, past fields where men and women thresh paddy, is a dirt track that leads into this village of Lodh Rajputs — “80 per cent,” says pradhan Rajpal Singh. “The rest are Dalit and Muslim families. This is not a rich village. Most of them are farm labourers or work in factories in Rudrapur. Today is a Sunday, but you won’t find the men around because they are all away at work.”

The village has two schools — a government primary school and a higher secondary school the sarpanch’s father Karan Singh owns.

“Is the government doing another survey?” asks a woman at a narrow bend from where the ASER team takes a left turn.

Maurya, who is in charge of three districts for ASER, stops to explain: “You send your children to school. The government puts in so much money. Shouldn’t they know if the children are learning? Don’t you want to know?”

“Haan, pata to karna padega (Yes, we must find out),” says the woman, joining the cavalcade of children who are trailing ASER surveyors Hardesh Kumar and Vivek Dubey.

In their 20s, Kumar and Dubey are training to be primary teachers under the government’s District Institute of Educational Training (DIET). They have been here since 8.30 am, having already met the sarpanch, handed him a letter from ASER explaining the survey and drawn up a rough map of the village after an hour’s walk. By evening, they have to cover 20 households.

“We select the houses based on a simple baayein haath ka niyam or left-hand rule. The map of the village is divided into four sections and in each section, the surveyors visit every fifth household on their left,” says Sunil Kumar, the ASER coordinator in Uttar Pradesh, turning left into another narrow lane.

“Iska bhi survey karwadijiye. He reads well,” says a woman, thrusting her child into the lane as the ASER team walks past her house. The child does a Jack-in-the-box and disappears.

The parade of children and their curious mothers stops two houses later, at Radha Devi’s house. Her husband, a daily-wage labourer, is not home. A cot is dragged from the courtyard into the only room the family of eight shares.

Kumar and Dubey get down to work. How many children? Six — three boys, three girls. The eldest, Devaki, is 18, so she won’t be part of the survey, but she takes charge and answers for her mother. TV? No. Electricity? No. Do they have books in the house? No. Mobile phone? No.

By now, the neighbourhood children who have pulled themselves out in the middle of play are jostling at the door. The women are here, too, to see if Radha Devi’s children can read.

It’s Ravi’s turn. The nine-year-old is so embarrassed he rolls the ends of his shirt and stuffs it into his mouth. “You can’t read this way,” smiles Sunil. By now, Ravi is having a laughing fit. “Wipe your nose and start reading, babu. Stop laughing,” says Devaki, gently holding her little brother down as he bounces, shirt still in mouth. After some coaxing, the shirt is pulled back into place.

Ravi holds the sample paper that has been quarter-folded for him to read the Hindi para. He only manages a couple of alphabets. “Prarambhik (beginner),” calls out Dubey. Kumar makes the entry against Ravi’s name. Ravi and two of his siblings had dropped out of school a few years ago. After each of the five children in the house has been tested, the team moves on.

“Only two of the children we have surveyed so far have managed to read the paragraph,” says Dubey, leaving Radha Devi’s house. “A boy in the first house we went to and Sujay. Remember Sujay? The brother of that girl Kusum, who was mixing the cowdung?”

Sujay says he is 11, but he is already in Class VIII. He had prompted Kusum as she struggled to read, but she had been too nervous to notice. When it was his turn to read, he had sat down on the same cot, Maurya by his side, clutching another of the sample papers. His voice hoarse and thick with excitement, he had read out: “Aaj mamaji ghar aaye…”

By then, his mother Vimla Devi had heard of the survey and had rushed back from the fields. The women were clapping and cheering when she came.

“Ladka pass ho gaya,” said one. “He is the only bright kid around,” said another. Sujay had breezed through the next few pages — words, alphabets and math, using his fingers rapidly to do three-digit multiplication and division, slowing down only in the English section.

…

The Right to Education Act, 2009, managed to get children to school, pushing up enrolment levels and making sure schools were held accountable for their infrastructure — playgrounds, toilets, kitchens — but it had no way of ensuring learning levels improved. As ASER first found out in 2011, levels of reading and math had, in fact, dropped in many states since the RTE came into effect. In 2008, the proportion of children in Class III who could read a Class I text was 50.4 per cent, but that dipped to nearly 40.2 per cent in 2013.

“Kusum must have been in Class V when the RTE came into effect. Since the Act did away with exams and assessments and said children can’t be held back, she must have gone all the way up to Class IX, without ever being tested,” says Sunil.

In February 2013, in response to a question in Parliament on declining learning levels in rural schools, then HRD Minister Pallam Raju had dismissed ASER as a “cursory assessment” brought out by Pratham and gone on to say that the NCERT does its own “detailed, periodic” National Achievement Survey that has “revealed improvements in the overall learning levels, even though achievements remain low”. It’s a line the government has stuck to each time the question of low learning levels has come up in Parliament — soon after the ASER report for 2012 was released in January last year, the question came up at least 15 times over the next two months. This year, the question has already come up twice in Parliament and the government has made the same argument.

“Our reports are not a way to say the government doesn’t do its job. It’s more important that the government sees there is a problem. Once you do that, solutions are not hard to come by,” says ASER Director Rukmini Banerji.

Over the years, ASER has proposed simple solutions such as grouping children across grades based on their learning levels. “For instance, if there are children who can’t identify alphabets in Classes I, II and III, bring them all together and teach them. That’s how Bihar’s Mission Gunvatta, for instance, works,” says Ranajit Bhattacharyya of the ASER Centre.

…

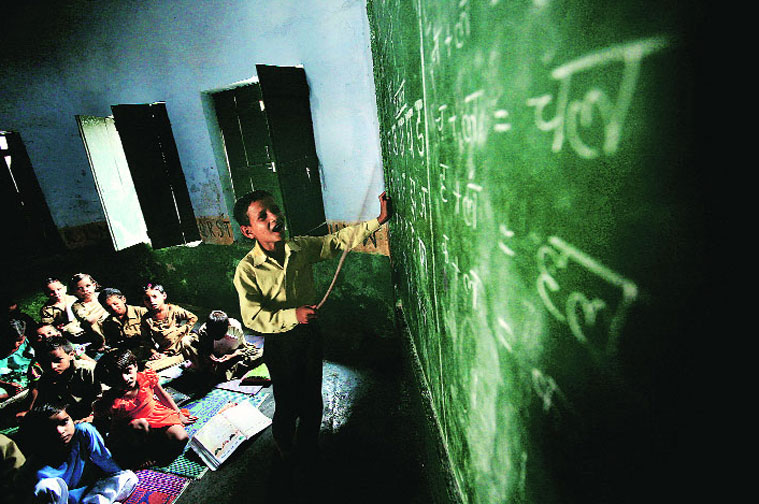

Imran is in Class V. Rajbir, a year younger, is in IV. But they sit in the same classroom, side by side on the floor, in the front row. The ASER team is in the primary school of the village on Day 2 of the survey to collect data on the school.

While Dubey and Kumar fill up their forms and check the attendance registers, Maurya holds a mock quiz in Class IV-V. “Bharat ka pradhan mantri kaun hai?” “Narendra Modi,” the class shouts in chorus. The next few questions get enthusiastic replies till Maurya gets to “up-rashtrapati (vice-president)”. Silence. As Maurya leaves the room, Imran pulls out two sheets of paper, runs his finger over a long list of questions and finally reads out:

“Hamid Ansari.” He repeats the name and puts the sheets away in his bag. “I stood second in a GK competition at the nyay panchayat level and Rajbir came third. There were 40 children from different villages. Our teacher gave us this list of 60 questions to prepare. I took home 30 and Rajbir took the other 30.”

While they study together in class, they don’t go to each other’s homes, Imran says. “Hum bhai nahin hain na. Rajbir Hindu hai aur main Musalman (We are not brothers, you see. He is Hindu and I am Muslim).”

Dubey and Kumar now take a head count of the number of students in each class. “Of 171 students, 112 are present today. The idea is to make sure the attendance isn’t inflated,” says Dubey. The school has classes from I to V, two teachers who are both present for the day and two para-teachers who are both on long leave. The principal’s post has been vacant for a while.

“You talk of learning levels? There are just the two of us. Look at the amount of forms we have to fill up — admissions, scholarships. And then, do the rounds of banks, open bank accounts for children, uniform distribution… I am an Urdu teacher, but I teach everything… or nothing at all,” says Saira Jamal, the senior teacher who doubles as the school in-charge.

The cook walks in and announces that the school kitchen has run out of sugar for the mid-day meal of sweet dalia. So Imran is called from Class V. “Go, run and get some sugar from the pradhanji’s house,” says Jamal.

Dubey and Kumar take a round of the school’s three classrooms, the toilets and the kitchen, and make entries. Class I and II have been clubbed together, Class III is in a room a little distance away and Class IV and V sit together. The anganwadi children walk in and out of classes. Rakesh Kaushal, 26, practically the only teacher, does the rounds of the three classrooms, spending a few minutes in each. “When the teacher is not around, I teach. Ma’am samajh ke,” says Imran, beaming, just as Kaushal walks over to Class III.

“There are different levels of learning in each class. This class, for instance, will have a couple of good students and many others who can’t do the basics.

That’s also because a lot of these children are too young to be in school. Their parents fudge their ages and get them admitted hoping their children will at least get to eat the mid-day meal which, for some, is the only proper meal of the day,” says Kaushal, a post-graduate in political science.

Around noon, Imran is back home and has changed into a pair of shorts, still wearing his uniform shirt. He lives in a one-room mud-house at the far end of the village with his parents and four siblings. His father Shoaib Ibrahim repairs shoes at Swar Camp in Rampur, but these days his asthma keeps him mostly at home. “My eldest son is a barber in Delhi and my youngest child is three. All my other children study. My eldest daughter is in Class IX and Imran and his younger brother go to the primary school in the village. My life has been wasted. My father too spent his life this way. I hope my children lead a better life. At least the teachers say good things about them,” he says, his tired eyes crinkling in a smile as he ruffles Imran’s hair. “He is the naughtiest.”

On the way out of the village, Maurya does a quick, back-of the-envelope calculation. “Of the 39 children we surveyed yesterday, only 12 could read a story, 2 could read paragraphs, 3 could read words, 10 only identified letters and 11 were at the beginners’ stage. That means, 70 per cent children couldn’t read a story,” he says.

That’s where this story begins.

(The name of the village has been withheld and names of the respondents have been changed at ASER’s request)

Apr 23: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05