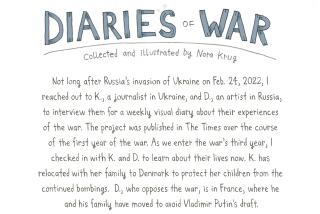

Roman Muradov’s graphic novel loss of innocence (in a sense)

Roman Muradov’s first graphic novel, “(In a Sense) Lost and Found” (Nobrow: 56 pp., $19.95) is a strange and beautiful book. Think Kafka as adapted by F.W. Murnau.

It begins with a nod to “The Metamorphosis”: “F. Premise awoke one morning from troubled dreams to find that her innocence had gone missing,” Muradov writes, echoing perhaps the greatest opening line in literature. When the character goes down to breakfast, we meet her father, who may or may not be “a gigantic insect”; all we see are his antennae, wavering behind a newspaper.

Muradov has drawn for the New Yorker, Time, GQ and the Wall Street Journal, among other publications; he did the cover for the 100th anniversary edition of James Joyce’s “Dubliners,” which came out earlier this year.

His is something of a nightmare world, all jagged angles and disconcerting juxtapositions. Here, innocence is a physical thing, an artifact, one that can be lost or sold. Ordered back to her room, F. (another Kafka reference?) climbs out the window and enters the city, where she faces the approbation of her fellow residents. Page after page features little or no dialogue, just a tangled swirl of images, inner and outer world colliding on the page.

Eventually, she ends up at a bookstore, where the jaded proprietor gives her a lesson in what it means to grow up. “The only way to get through life without losing your mind,” he says, “is to accept.”

“God, you’re depressing!” she tells him. “So is life,” he replies.

For Muradov, the idea is to turn the allegorical into the actual, to create a world in which innocence is a physical thing, an artifact, that can be lost or bartered away. In that regard, he is like Kafka also; what else is poor Gregor Samsa than a metaphor brought to life? At the same time, he is more than that, a three-dimensional character in an articulated universe. This is also true of F. Premise.

As the book progresses, she comes into herself, seizing what we might call a kind of agency. “You left the familial table a mere premise,” a merchant tells her late in the narrative, “and now you’re bursting with dimensions” – an assertion brought to full fruition by the dark and eerie lines of Muradov’s art.

For F., the loss of innocence leads her to something deeper; a reckoning with herself. As such, “(In a Sense) Lost and Found” is a coming-of-age saga, in addition to everything else. The book is rife with wordplay, a delight in language as sound, as music, which mirrors the movement of the art. All of it suggests the world is much weirder, much more beautiful and dangerous, than mere innocence allows.

This is the conundrum, the tension (or the balance) with which we all must come to terms. It’s the strength of “(In a Sense) Lost and Found” that it evokes both sides of this equation: a song of innocence and experience.

twitter: @davidulin

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.