GB Patent Number: GB2509856

Granted to: C & C Marshall Limited

There is ongoing discussion about reducing our energy consumption. Most recently, this has reared its head regarding the need for energy-efficient domestic appliances and in particular, the EU’s ban on high-power vacuum cleaners, with talk of other devices in The EU Commission’s sights.

For the green consumer, there are many choices available when looking to purchase an energy-efficient device.

Only recently, I went through a process of swapping a rather large number of halogen spotlights for more environmentally friendly LED bulbs.

A common consideration in such situations is whether the initial cost is justifiable, based on the long period required to claw back the extra expenditure on the greener and often more sophisticated product. Hence, when looking for this month’s patent, I was intrigued to find C&C Marshall Limited’s UK patent 2509856 which was granted on 27 August 2014. At first glance, the modestly-titled “Voltage control apparatus” patent appeared to be one of the most overwhelming no-brainer energy-saving innovations that I had seen for some time.

This patent relates to electrical power consumption. Mains electrical supply voltage varies from one European country to another in the range of 220V to 240V. For the sake of manufacturing simplicity, many consumer electronic and electrical goods are produced as a single model which can be used throughout the whole of the European market. To cater for the differing mains voltage levels, these products are designed to operate at the lower end of the range – around 210-220 V.

The patent discusses the following problem. A consequence of using these products in the UK, where we use a standard nominal voltage of 240V, is that the top 20-30V of the mains supply voltage is surplus and, as a result, is wasted as heat. Have you ever wondered why the transformer for your laptop gets so warm? Apparently, this 20-30V is likely to be the answer.

The worrying thing about this situation is that it is being repeated many times over in homes and businesses throughout the country. Unthinkable amounts of electricity are being wasted as a result.

Voltage optimisation

To address this problem, the concept of ‘voltage optimisation’ was developed. This involved using a step-down transformer between the grid power supply and a consumer unit (that’s the ‘proper’ name for the fuse box under the stairs) to reduce the voltage throughout a home to 220V. However, a problem with this approach is that it is not always appropriate to reduce the mains voltage for an entire property, since some devices require the full 240V to operate.

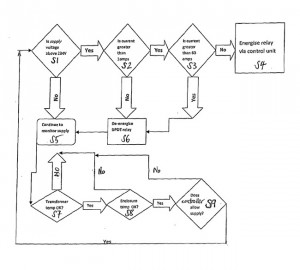

C&C Marshall’s invention solves this particular problem by providing a voltage control apparatus comprising:

- An input for receiving an electrical supply with an associated input voltage

- A voltage control system that is arranged to receive the electrical supply from the input. In turn, this selectively reduces the input voltage

- An electrical output arranged to provide a supply to a consumer unit. This output should have a voltage in accordance with the selectively reduced input voltage

- A monitor arranged to check a current being drawn into the voltage control apparatus for determining whether the electrical output should be connected to the received electrical supply or the output supply. This monitor should have a reduced voltage in accordance with the reduced input voltage and the voltage control means. This then allows the device to bypass the step-down transformer and provide the full 240V when necessary.

Having given this patent some further thought, I began to doubt the effectiveness of this invention in general. This is because many devices are very happy to receive an input voltage anywhere between 220 and 240V. Some such devices include kettles, ovens, washing machines, immersion heaters, electric showers, tumble dryers and even fridges and freezers, which all convert electricity primarily into heat (even in the case of fridges).

Let’s consider a kettle, as an example. If I want to boil water for a cuppa, I need to heat a volume of water until it boils, for which my kettle must produce a predetermined amount of heat from its electricity supply. The effect of reducing the input voltage will, in fact, mean that the kettle will take longer to boil. Technically, this will use more electricity overall since a longer boiling time will mean more heat dissipation whilst the water is being heated. So in this case, a lower mains voltage is less advantageous to the environment.

Similarly, the other heat-producing domestic appliances will work less efficiently at a lower input voltage, since they will take longer to get the job done. So C&C Marshall’s voltage optimiser is not going to make me any savings there.

Energy wastage

Hang on a minute, I hear you say, what about those devices which are truly designed to operate at 220V, where there will be less energy wastage with the C&C device? This is where things begin to get murky. Practically speaking, televisions and computers, for which C&C’s device would provide a benefit, don’t consume a large amount of energy compared to the heat-producing devices listed above. This means that in reality, devices where there would be a benefit would account for only a small proportion of my overall electricity consumption. Hence my question is, will the invention described in this patent provide me with much of a saving after all? All comments and thoughts are welcome below…

An interesting thing about this patent from a patent attorney’s perspective is that the patent took a mere four and half months to grant from the date that it was lodged, which goes to show how quickly patents can be examined and granted when required – a real efficiency by the UK Patent Office, if nothing else!

Michael Jaeger is a patent attorney at leading UK patent and trade mark attorneys, Withers & Rogers LLP.

Electronics Weekly Electronics Design & Components Tech News

Electronics Weekly Electronics Design & Components Tech News