OPINION:

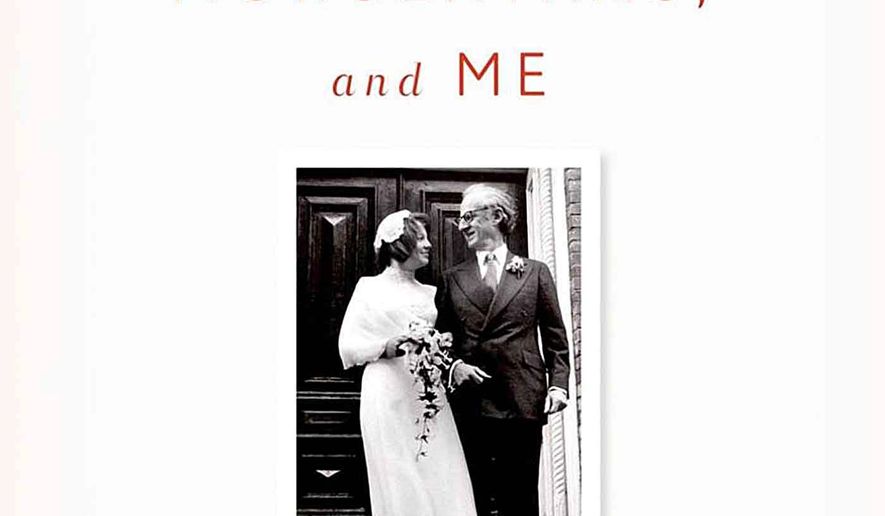

TIMELESS: LOVE, MORGENTHAU, AND ME

By Lucinda Franks

Sarah Crichton Books/FSG, $28, 389 pages, illustrated

Although Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Lucinda Franks was born long before the term “too much information” became a cliche, this autobiographical hurtle through her life and marriage shows her to be a veritable personification of the phenomenon. I don’t think there will be many readers who do not find themselves shrieking those three words or their even more common abbreviation, TMI, as they face the onslaught of larger subjects and the minutest of details better left in private.

That’s a great pity for many reasons. Most of them have to do with invasions of privacy: Leaving aside the propriety of her being entitled to bare her innermost all, what about the others’ plundered here? But there are a certain number of insightful and telling nuggets buried deep among all this stuff you really don’t want to know and, quite frankly, should really not be exposed to.

Happy love stories are notoriously difficult to tell — ask the masterly Tolstoy. Ms. Franks deflects some of that problem by going into the gory details not only of her and her husband Robert Morgenthau’s grave illnesses, but of her parents’ and even his first wife’s. She dwells on the difficulty her would-be stepchildren had in accepting their father’s marriage to her to an extent that is discomfiting.

However, for all the lip service to respecting their — and their father’s — devotion to the late wife, the author’s focus is on her success in pushing Mr. Morgenthau to override their wishes and marry her. Here, as so often in this book, whether discussing her professional or personal life, she is unpleasantly boastful.

That brings one to the vexed question of tone. I’m not sure if there is a right tone for pouring forth everything from smoking hashish to taking the reader right into the bedroom and beyond, but I think it is safe to say that the one adopted by the author here is about as rebarbative as you can get. She manages to combine the worst aspects of adolescent defiance and immaturity with an arrogant sense of entitlement to do whatever comes into her head.

A case in point is taking her “hash stash” to her future husband’s home and partaking. What can you say? She glories in the unfiltered revelations of such escapades, which, like the many details of Mr. Morgenthau’s skills as a lover, do not so much affirm her constantly stated declarations of devotion as call them into question. Similarly, Ms. Franks’ forays into pop psychology and her Procrustean propensity to identify Mr. Morgenthau with her father and herself with his mother, however comforting to her, should, like so much in this book, have been kept to herself.

So unpleasant is all this that one turns with relief to the welter of name-dropping. Sometimes this shows Ms. Franks’ parochial prejudices, as in her account of a dinner at the Reagan White House. Her reflexive pigeonholing of the president as anathema and her gratuitously nasty assessment of the first lady are not only tiresomely predictable, but have the unintended effect of canceling out any sympathy you feel for the snubs she has endured along the way up.

Sometimes, she can surprise pleasantly, as in her warm portrait of Ariel Sharon, whom she entertained at her home in New York and whose farm in Israel she visited. She takes no prisoners in showing the prejudice some of her guests showed toward Sharon and reveals his skill in dealing with them and his overall charm and likability. If only there was more like this and less of all those unfiltered and cringe-inducing revelations.

The author should have followed the advice in one of John Donne’s most famous poems. Notwithstanding being dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, Donne wrote some of the most powerful love poetry in the English language, much of it explicit enough to shock even students hardened by today’s coarse culture. One of his lovers utters lines Ms. Franks should have taken to heart: “T’were prophenation of our joys / To tell the laity our love.”

If she really does love her husband as much as she repeatedly says she does, can it not have occurred to her that telling everyone all about their most intimate moments does profane that love? Owing to her lack of restraint or taste or propriety, what is supposed to be a celebration of something extraordinary ends up being instead a desecration.

Martin Rubin is a writer and critic in Pasadena, Calif.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.