- India

- International

The Big Picture: A school apart

Until last year, Amboli village celebrated Independence Day at its panchayat school. That was before it realised 32 HIV+ students were on its rolls. A year on, they are the only children left.

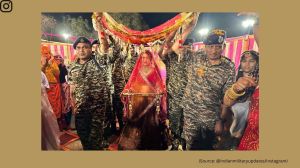

Until last year, the panchayat school in Amboli in Surat district had 210 students; now there are 32. (Source: Bhupendra Rana)

Until last year, the panchayat school in Amboli in Surat district had 210 students; now there are 32. (Source: Bhupendra Rana)

Until last year, Amboli village in Surat celebrated Independence Day at its panchayat school. That was before it realised 32 HIV+ students were on its rolls. A year on, they are the only children left in the school.

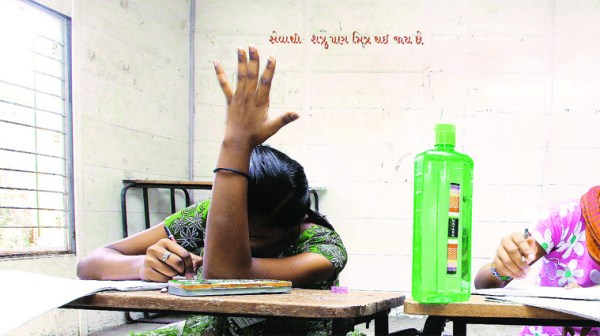

The front bench in the middle row. That’s Shilpa’s favourite seat in class. This is where the Class VIII student sits every morning with her friend. The rest of the classroom is empty. When Shilpa speaks, her voice bounces off the empty walls of the room: “Ma’am, what does ‘sowing’ mean,” she asks.

It’s 12.30 pm, an hour to go for lunch break at the panchayat-run primary school in Amboli village of Gujarat’s Surat district. This is the fourth period and class teacher Chetna Vekarya explains: “During the monsoon, farmers dig the soil and plant the seeds. This is sowing.”

Next door is Class VII. This room looks more filled out — eight children huddled in three rows facing the teacher. Class V is next, with four children. Class VI has three; the fourth child has been unwell for a few months. Next, past the staff room, is Class IV: eight students here. The rest of the students are bunched together in one room — one of Class I, two of Class II, three of Class III. It’s an easy count: 31 children in all. All girls. All HIV+.

The youngest child at the school is six years old while the oldest is 14. Twenty of them are orphans while the others have one surviving parent. (Source: Bhupendra Rana)

The youngest child at the school is six years old while the oldest is 14. Twenty of them are orphans while the others have one surviving parent. (Source: Bhupendra Rana)

Last year, the co-ed school had 210 students. Where are they now? The school isn’t stopping to ask. Instead, the five teachers and 31 students faithfully stick to their daily timetable — nine periods, the lunch break at 1.30 pm, games period and the eagerly awaited final bell at 5.30 pm.

But every once in a while, the thought of her missing classmates bothers Shilpa. Like it did on Independence Day this year, when principal Tara Patel hoisted the flag with six teachers and 32 students. Until last year, the school ground would be packed to capacity. The entire village, teachers and the school would turn out in full strength. This year, the celebrations were held separately. The villagers were simply making a point: they didn’t want to be associated with a school that had taken in HIV+ children.

Shilpa and the 31 other HIV+ students, who joined the school in June last year, are all residents of Janani Dham, a hostel for HIV+ girls in the village that’s run by P P Sawani, a Surat-based business group.

Until then, the children — from different districts of the state, some from as far as Saurashtra — had been studying at the panchayat primary school in Punagam area of Surat district and stayed in a rented house near the school. Nobody knew they were HIV+, so life was normal. Then the Sawani group bought land in Amboli, built a hostel and shifted the girls here a few years ago.

For the 32 girls, everything seemed perfect in the beginning — new school, new friends. But when the Janani Dham was formally inaugurated and several HIV awareness banners and posters of the Gujarat State Network of People Living with AIDS were put up at the hostel and at different places in the village, villagers realised that this was no ‘ordinary’ hostel.

Four days after the girls joined school, villagers met principal Tara Patel and threatened to pull their children out if the new students weren’t asked to go. Some of them staged a dharna outside the school for five days. Surat district panchayat president Ashwin Patel, Health Department officials, district development officer Remya Mohan and then collector Jayprakash Shivhare tried to pacify the parents, but the protests continued.

Natu Vasawa, a farm labourer in Amboli who shifted his son from the school to the Kathor village government school 3 km away, says, “The school, health officials and panchayat members say it is safe for our children to be studying, playing and eating with these other children. But what if the children fight, one of the HIV+ students is injured and her blood infects our children? The teachers and the staff can’t be with the students all the time. We don’t want to put our children’s lives at risk.”

But the district administration and the school stuck to their decision that the 32 girls would study here. “When the villagers were agitating, we brought it to the notice of the state government. We were told not to succumb to pressure and discriminate against the children,” says Shivhare, the former collector who is now in Dangs district.

Every morning, the girls set off from their hostel at 10.15 so that they are in school by 10.30. The older girls are up at 6 am, get the younger ones out of bed, fold their bedsheets and pile them up in the cupboards. Shilpa and three other girls who are in their teens take charge of the younger ones. In half an hour, the kids are all ready — their hair neatly pulled back and braided. Uniforms are not compulsory, so the girls wear regular clothes and slippers.

Shilpa has to take three pills under the strict supervision of the hostel warden who ensures that nobody misses their medicines. “I don’t like these pills. They taste bad. But our warden tells us that if we are not regular with our medicines, we will fall ill,” says one of the girls.

After breakfast, Shilpa readies her school bag and waits at the hostel ground where all the other girls assemble. They then walk down to school.

For the children, the walk seems longer than the 500 metres that separates the school and hostel. The girls say they usually encounter hostile village children on the way and that one of them recently flung a stone at them, injuring a little girl. “Serves you right. It was because of you that we had to leave our school,” the boy is said to have told them before running away.

“Some of the village boys say mean things about us, but our warden has told us not to pay any attention. We are a little afraid of these boys, but there is no way out,” says Alpa who studies in Class III but sounds way older than her nine years.

“The village boys are angry with us because they had to leave school. We told them to come back and study with us. We told them HIV doesn’t spread simply by studying or playing together. But they don’t like us,” says Shilpa.

As she walks to school, Shilpa tells her story. Her father, an autorickshaw driver, died of AIDS when she was three. Five years later, the disease took away her mother too. The virus spared her elder sister, who is now married. “After my parents died, I stayed with my grandmother and uncle. Once, when I fell ill, they got my blood tested and learnt that I was HIV positive. I was no longer allowed to play with my uncle’s children and couldn’t share my bed, clothes or utensils with anyone else. Five years ago, my grandmother dropped me off at Janani Dham and I have been here ever since,” she says.

On Sundays, Shilpa’s sister and grandmother call her and they chat on phone. On festival days or once every three months, they drop by at the hostel to meet her. For Diwali and during summer vacations, the girls are allowed to visit their relatives. Shilpa says the school counseled her relatives and so, she now gets to play with her cousins when she visits them.

Like Alpa, Shilpa too is wiser beyond her age. “I don’t know much about the disease — how is it caused, etc. But I know it spreads through blood, when a healthy person gets blood from someone who is HIV+; not by playing together or eating together or sitting together. I am fit and I can run as well as play. I play cricket with the girls. Dhoni is my favourite cricketer,” she says. She goes on, without prompting: “We watch TV in the hostel. I love watching movies. My favourite actress is Sonakshi Sinha.”

At 1.30 pm, the shrill electric bell goes off. It’s lunchtime. There is no mad scramble out of the classrooms, no swirling dust in the playground, no pushing and shoving, just silence. Slowly, the children appear at the doors of their classrooms, in ones and twos, and sit outside, in the verandah.

The school has a meal schedule — khichdi and a vegetable dish on Mondays, thuli (a sweet dish) and vegetable curry on Tuesdays, dal and rice on Wednesdays, roti and dal on Thursdays, dal dhokli (dal and dumplings) on Fridays and dalia porridge on Saturdays. Shilpa and the older children take charge — the younger ones are made to sit on the floor, plates are laid out, and food served. Today is a Thursday, so little Alpa gingerly dips her roti in her dal. She likes khichdi better, she says.

After everyone has eaten, a group of five children collects the plates and washes them while another group sweeps the floor. A few girls walk back to the playground. Some play kho-kho, others play kabbadi.

Vaishali, 13, of Class VII, says they have learnt to deal with injuries on the playground. “Two days ago, a girl fell and her head started bleeding. I washed my hands with diluted Dettol, wore gloves and dressed her wound. I know how to do that — first clean the wound with disinfectant, apply Soframycin ointment and wrap a bandage,” she says confidently. “But we do not allow teachers to dress our wounds — we know our blood is dangerous”.

The children make regular hospital visits to Surat for checkups. “The doctors there tell us that HIV can be checked with timely treatment and exercise,” says Vaishali.

Her friend Vinita, 13, says, “I want to grow up fast, own a good house, a car, a bike… I know I will get all this only if I get a good job. I am not afraid of death. The doctors have told us that there is nothing like death in this disease.”

Sitting in her room, principal Tara Patel — who has been with the school for 20 years — feels the silence around her more than anyone else. “Earlier, there was no space here and now there is a lot of space,” she says. But she is proud to have stuck by her decision to rally round the 32 children. “Our youngest child is six years old while the oldest is 14. Twenty of them are orphans while the others have one surviving parent. We treat them like our children. Every morning, we ask them if they have taken all their medicines,” says Patel.

The school staff has been told to be sensitive while handling the children. “All of them take heavy doses of medicines and sometimes, some of them feel drowsy. We let them put their heads down and rest for half an hour or so. These children are very brave and know about their disease. They don’t hide it,” says Ramesh Patel, the science teacher.

Mohammedbhai Malek, who has been teaching at the school for 13 years, says, “In the last one year, we have become very close to them. We miss them when they go home for their vacations.”

The bell rings at the end of the 45-minute recess and the girls saunter back to their classrooms.

As she walks back, little Alpa recalls, “For the first three days, the village boys sat next to us, we played together. Now we are alone in the school.”

“Alone” in a class of three. That’s not how Alpa should have been studying. That’s not how school should have been for Alpa.

(Names of the students have been changed to protect identities)

May 05: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05