Analysis: Deradicalising Brits in Syria

- Published

- comments

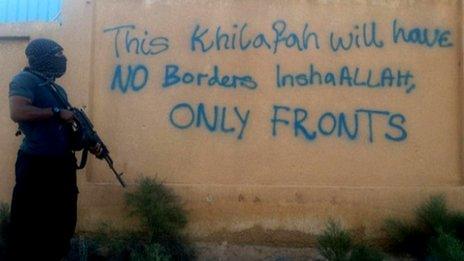

The British fighter stands by some graffiti on a foreign battle-field.

"This Khilafah will have NO Borders... ONLY FRONTS."

As mission statements go, it is pretty clear: the so-called "Islamic State" fighters want to push the boundaries of their seized land further and further - and it's an ideology shared by hundreds of men from the UK and other Western nations who have joined the jihad in Syria and now Iraq.

At least 500 people from the UK are thought to have gone to Syria to fight - and many of them have already returned.

Some people in Muslim communities believe that quasi-official estimate to be a woeful underestimate. They have seen significant numbers of youngsters motivated to go to Syria either out of anger or because they have bought into the propaganda pouring forth on social media.

But what happens if they come back? Does the brutalising effect of the war - and the ideology involved - pose a threat?

Potential threat

The British legal definition of terrorism includes fighting in conflicts overseas and the UK's position is quite clear: anyone who gets involved in fighting could be guilty of a terrorist offence.

So far that has been the key public prong of the counter-Syria strategy. More than 60 people have been arrested on return to the UK either on suspicion of involvement in jihadist fighting in Syria or of helping others to do so.

There have been a handful of convictions involving men who were accused of receiving terrorism training. There are more trials pending where suspects deny that their activity in Syria amounted to terrorism.

Is it practical or even possible for the police to charge everyone who returns - and would locking them up solve the problem?

Prosecutions such as that of Portsmouth man Mashudur Choudhury get reported by people like me because trials happen in public.

But in reality there is a lot of discreet effort behind the scenes to try to work out what to do with others who have been radicalised or brutalised by Syria.

Let's look at what could happen to the typical returning fighter (assuming that they want to return, given that many say they won't).

If the Security Services know who they are - and they often do - you can expect the individual to be stopped almost immediately as they enter the UK. Where there is immediate evidence of a crime, the police will charge. But MI5 officers will also want to speak to returnees on more discreet terms.

MI5's goal is to work out who is a potential threat to national security, who could become a danger on the streets.

Investigators often ask returning suspects about their activities, networks, experiences and ideology. They want to build up a picture of the individual and whom they are aligned to.

They will ask returnees to provide further help. But what happens if they get rebuffed? If the police can't step in with a criminal charge, and the individual is considered a risk of violent extremism, there are other routes.

Deprogramming

The Channel scheme is part of the UK's counter-terrorism strategy and it is a process that challenges violent views. To all intents and purposes it is an attempt to deprogramme and rewire an individual.

The target is drawn into a process of analysing their views and their place in the world: theologians will challenge their beliefs; other experts, such as psychotherapists, will be involved in addressing social and emotional problems that lie at the root of their anger.

A crucial part of the process is to dismantle the "us and them" mentality that extremists use to drive a wedge between vulnerable Muslims and the rest of society.

Demand for Channel's services has increased. In the last financial year its teams received 1,281 referrals - a 70% increase on the previous year. The Association of Chief Police Officers has not provided a figure for how many of those cases relate to Syria.

So Channel is a long and complex process - and it has been successful and turned some lives around.

But it has its limitations. Not everyone will be changed. People could leave Channel holding exactly the same views they started with.

Their participation is effectively voluntary. The work is so sensitive and challenging that there are only so many experts who can be called upon to carry it out.

So the nightmare scenario is that it becomes overwhelmed if, all of a sudden, hundreds of Brits came home.

And it's that fear of mass returns that really concerns security chiefs. Metropolitan Police Commissioner Sir Bernard Hogan-Howe says the UK would face a "challenge" if hundreds did come back - and that he is putting plans in place.

After the Woolwich murder of Fusilier Lee Rigby, the government promised a renewed focus on radicalisation. Ministers have been busy confiscating passports and have persuaded internet giants to stamp out extremist videos.

But critics say this has not backed up with enough cash or action to get at the roots of the problem. The original preventing extremism schemes, launched by Labour after the 7/7 attacks, were criticised for lacking focus - but the coalition has been accused of prevarication and of shunning some community groups that had previously worked well with officials on trying to identify the most vulnerable individuals.

'Blowback'

There is another prong to the counter-jihad strategy: one led by communities themselves.

You don't see them on TV but up and down the country there are imams and other community leaders who have grasped the Syrian nettle and are trying to prevent people from going. We have also seen the beginning of community attempts to challenge the jihadist narrative online.

Officials have correctly identified that women need to be supported in pushing the message. Specialist Preventing Violent Extremism police officers are working with them around the country.

Ultimately there is only so much that governments can do. Many young Muslims remain deeply sceptical about messages coming out of Whitehall because of what they regard as woeful double standards over foreign policy.

Some campaigners, such as pressure group Cage, say the threat of "blowback" from returning fighters has been exaggerated.

This argument has some traction for two reasons. Firstly, Syria fighters who have spoken to the BBC are adamant they're not coming home: they are in the land of jihad and they'll either build their new state or die a martyr's death trying.

Secondly, we have not seen a slew of terror convictions which draw a direct link between attack planning in the UK and Syria.

But that second point has echoes of where we were after 9/11. People dismissed the idea that the UK could be a target - until bombs exploded in London on 7 July 2005.

If, as the graffiti reads, some Brits in Syria regard their mission as pushing the frontier forward - security chiefs fear it will only be a matter of time before that threat comes home.