Editor’s Note: Neal Gabler is the author of “An Empire of Their Own: How the Jews Invented Hollywood.” He is currently working on a biography of Edward Kennedy. The opinions in this commentary are solely those of the author.

Story highlights

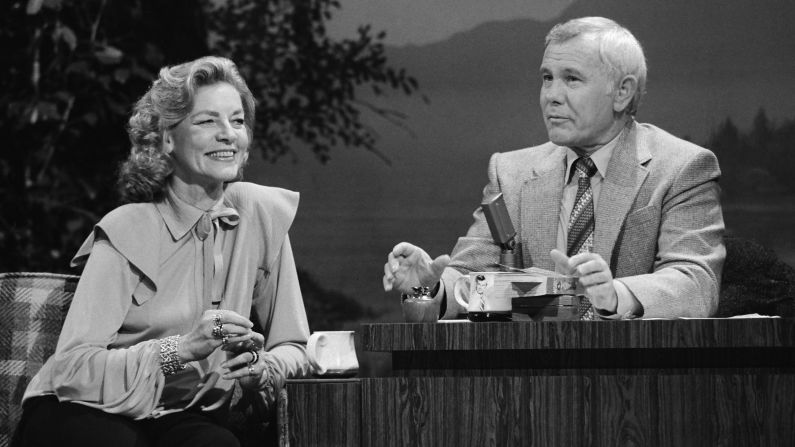

Lauren Bacall, a Hollywood icon, died on Tuesday at the age of 89

Neal Gabler: She would be defined by her marriage to the great actor Humphrey Bogart

He says self-possessed Bacall was the perfect noir woman, she had the right attitude

Gabler: Despite the razor's edge she brought to screen, her persona outlasted its time

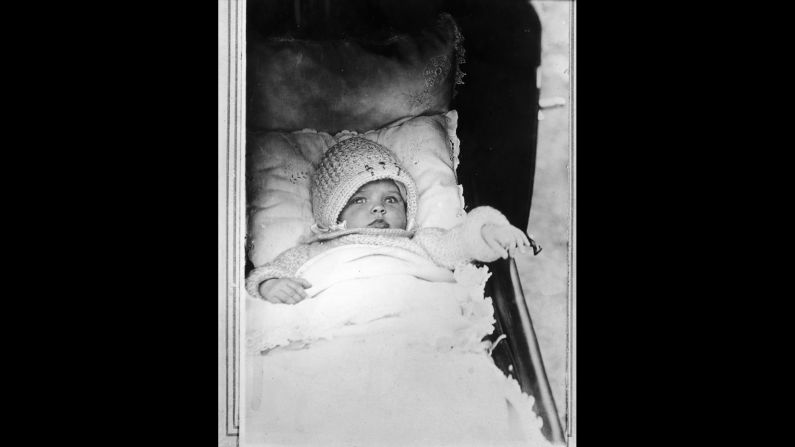

Lauren Bacall, who died Tuesday at the age of 89, always said, not altogether happily, that she would be defined by her relationship with her husband, the great actor Humphrey Bogart.

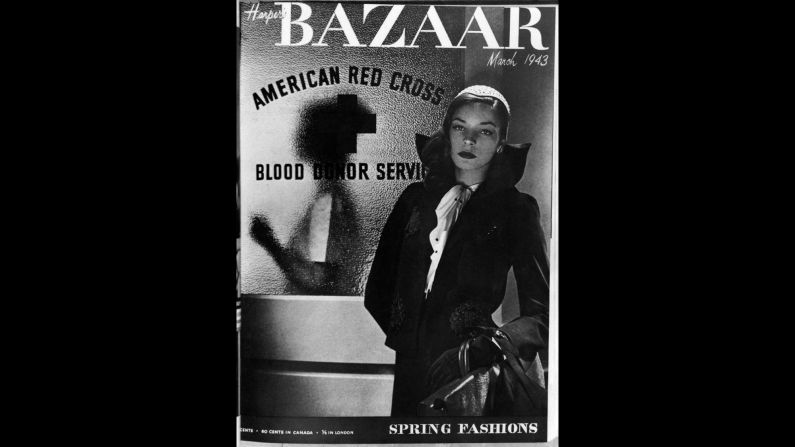

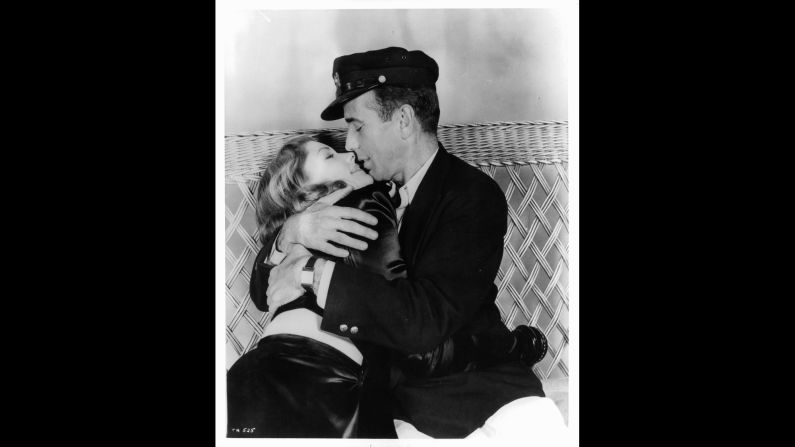

She was not entirely wrong. It is hard to think of Bacall without thinking of Bogart. When she first arrived on screen in 1944 in “To Have and Have Not,” at the ripe old age of 19, the thing that captivated audiences was not her beauty – there were lots of pretty girls on screen – so much as her preternatural steeliness. Here was a woman who could stand up to Bogart purring line by purring line, menacing look by menacing look, sneer by sneer, which may be why he wound up falling in love with her in real life. She was not a shrinking violet. She was a Venus flytrap.

But if Bacall was unflappable, she was different from her steely predecessors, the so-called tough “broads” of the 1930s like Bette Davis and Joan Crawford. They were victims of the Depression, victims of male dominance, victims of bad breaks, victims of life in general. Those things made them feral, which is not an adjective anyone would ever have used on the self-contained, self-possessed Bacall. They were at war with life, hoping to find some good man with whom they might be able to make a truce. Bacall didn’t seem to be at war with anyone, and she certainly didn’t seem to think she needed a man to fulfill her. In fact, she was pretty much unpossessable. She did things on her terms.

If you think of Davis and Crawford as curs, Bacall was a cat. She arose at a time when World War II was ending and film noir was beginning, and she was the perfect noir woman. Noir was a style of film, dark and edgy, but it was also an attitude of post-war ennui and cynicism.

In noir, you trusted people at your peril. Bacall embodied that attitude perfectly in films like “The Big Sleep,” “Dark Passage” and “Key Largo,” all of which co-starred Bogart. There was something slippery and unknowable about her, some sort of concealment, which fit the whole noir ambiance. And it wasn’t coincidental that the perfect noir woman was also the perfect complement and foil for the great existential hero of the movies, Bogart. She was the great existential romantic partner.

That attitude of hers seemed to arise from a personal grievance that Bacall developed growing up in New York as Betty Joan Perske, a Jew who was remade into a cinematic gentile by the anti-Semitic director Howard Hawks. As Bacall tells it in her first memoir, “By Myself,” Hawks was a Pygmalion who discovered her and then taught her how to move, how to talk (that deep, sultry husk of a voice) and how to act.

But the umbrage she felt toward Hawks in making her deny herself may have been the razor’s edge she brought to her performances. She was always forced to be in camouflage – a hidden Jew. She even raised her children as Episcopalians, Bogart’s religion, because she feared what might happen to them as Jews. For noir, the edge certainly worked.

Hollywood recalls screen legend Lauren Bacall

But the persona outlasted its time. Well before Bogart died of cancer in 1957, Bacall’s career had begun to slide, in part because noir had begun to slide, relegated to B movies. She was able to reinvent herself in romantic comedies like “How to Marry a Millionaire,” where she turned her sultriness into a kind of brisk efficiency, a no-nonsense woman for the 1950s, that contrasted with co-star Marilyn Monroe’s flouncy availability, but the glory days were pretty much over. In retrospect, she hadn’t been so much a star as she was a flare.

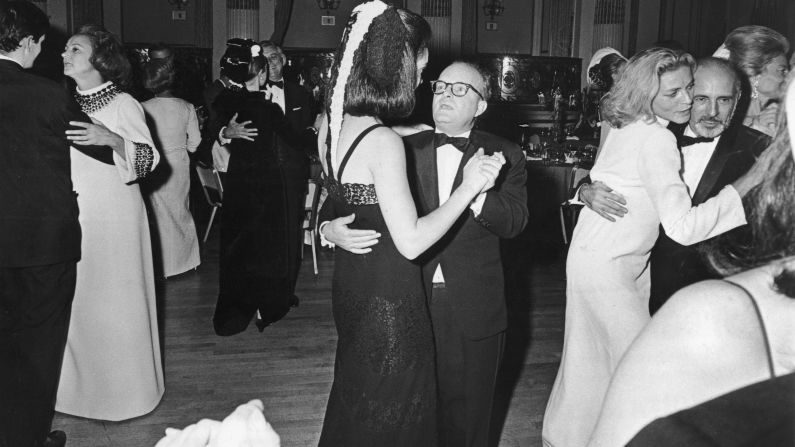

Her late great triumphs were on stage – in “Applause,” a musical adaptation of “All About Eve,” and “Woman of the Year,” a musical adaptation of the 1942 film of the same name, both of which earned her Tonys. Still, the fact that she was reprising roles originally played by Bette Davis and Katharine Hepburn respectively was a sign that Bacall’s own feline charm had not endured. In the end, she was a glamorous figure from another, darker era… and the wife of Humphrey Bogart.

Read CNNOpinion’s new Flipboard magazine