Is it hyperbolic to say that Gaza or Iraq or Syria or the Ukraine are the current Snowpiercers of the world?

Not if we count the mounting casualties and other horrific atrocities desecrating these warzones. Nor in such countries deemed to be at extreme risk of inflicting severe human rights offenses as Somaliland, Sudan, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, North Korea, Belarus, Nigeria, Yemen, Uganda, and China. The Snowpiercer in the film of the same name may be a train, but its circumnavigation of the earth's seven continents is analogous to the universality of conflict that marks, or has marked, every place that humans inhabit.

The Snowpiercers in the Realpolitik

As for Snowpiercer the film, the reviews are all in and the mainstream critics have near-unanimously showered accolades on South Korean director Bong Joon-ho for his enthralling depiction of the human condition plunged into a dark age of deprivation, sadism and unrelenting brutal conflict suggesting humankind sees to its own final solution. All of which means we are likely to see a second wave of cultural critics exhume the deeper moral and political implications tying such conditions to contemporary class relations in general and to the current outbreak of violent conflicts around the world in particular. It is no surprise, then, that some veteran cineastes may be wondering what all the fuss over a branded sci-fi entertainment can be about.

The fact is our post-9/11 era is without a serious cinematic masterpiece chronicling the terror and upheaval culminating in war--that is, a film that historicizes the era with a world view that summarizes our most relevant achievements and losses amid the remains of history--regardless of whether or not the most relevant view of history is also the most factual. It is the historical consciousness that dominates all art making in modernity, if not entertainment, which means to historicize Snowpiercer is to take it seriously as art.

Amid such a void in serious cinema, audiences turn to science fiction for its pregnant, if not always fully-formed, precognitions of the social diseases feeding real political conflicts in the making. Always the eager genre to sermonize moral positions on the most extreme malversation and abuses, science fiction has never been more starkly or boldly rendered than in Snowpiercer's openly political dissection of our capacity for sadomasochism. Blame it on our incomplete evolution--we share with lizards the limbic system of the brain that regulates such impulses as fear and aggression--and Snowpiercer succeeds in reducing its picture of humankind to its basest nature in a way few films before it has without desiccating to gratuitous violence. But though the film doesn't provide the kind of insight into the more complex, if rigid, ideologies that feed the human propensity for intolerance, sadism and annihilation, the coincidence of Snowpiercer's theatrical release in the U.S. with the escalating conflicts in Gaza, Syria, Iraq and the Ukraine invites corollaries to be made between the screen and the militarized zone.

For being without a more realistic reflection on war, we are an oddity. Like so many epochs, ours is a shard of history that has been rent from its former continuity by a willful cataclysm of unimaginable depravity and agony. But the serious, historicizing film that will translate the traumas and quests of the post-9/11 era into an iconography of contemporary warfare and class relations remains to be made. So far, only Kathryn Bigelow's Hurt Locker and Zero Dark Thirty count as masterpieces reflecting the international hostilities and competing ideologies of the post-9/11 era. But Bigelow's films depict individuals engaged in their own private battles respective to the war in Iraq and the war on terror without iconically capsulizing what became known as the battle of civilizations. For that matter, just as that battle began well before the attacks on the World Trade Towers and the Pentagon, the proliferate chain of international and civil wars disfiguring the Middle East today reminds us that battle hasn't ended with the death of Osama bin Laden.

We still await the singular work of art or entertainment that summarizes what new morality, ideology and culture is emerging from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, while articulating the myriad complexities and players of so great an intercontinental and crosscultural war zone. No doubt we anticipate too much if we expect the kind of cultural shift that mobilized the antiwar movement against the bombs dropped on Vietnam and Cambodia and became permanently mirrored in the scathing cinema of dissent ushered in with Robert Altman's MASH, Francis Ford Coppola's Apocalypse Now and Oliver Stone's Platoon.

Before Vietnam, the cinema of the post-World War era, cognizant that its viewers were still convulsing from the disclosures of concentration camps and the annihilation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, withdrew into the existentialist anxiety of Stanley Kubrick's Paths of Glory and the anti-colonialism of Gillo Pontecorvo's The Battle of Algiers. By contrast, the World War ll years were marked by near-immediate response from the international film industry, most of it made as nationalistic reaffirmation, of which Howard Hawks's Air Force and Roberto Rosellini's trilogy, Open City, Paisan and Germany Year Zero are the most memorable. Only after World War I did it take Western audiences as long as the Post-9/11 audience to see their histories immortalized by an emergent cinema, with Lewis Milestone's All Quiet of the Western Front and Jean Renoir's Grand Illusion. But then they were without our unprecedented digital capacity and production budgets.

There is nothing new about finding recourse in science fiction for expressions of our political and moral contingencies--especially those reflecting our deepest anxieties--which might otherwise not be seen in the light of screens outside of the news. In the 1950s and 1960s, sci-fi was the only mainstream vehicle for potentially subversive criticism of the mainstream culture, however much it was handicapped by B-movie budgets and reduced largely to parody and subtext. But from the 1980s to the mid 2000s--the era of our self-appointed "postmodernism"--dystopian science fiction became code for a cinema of left-leaning, if ironic, commentary on social ills that enthralled intellectual and mainstream audiences alike. The most prolific and ubiquitous visions of war during these decades, and more importantly, of the technology of warfare, are found in Blade Runner, Mad Max, Terminator, the Alien quadrilogy and The Matrix trilogy. But none of these dystopian sci-fi visions, as metaphorically satirical and analogous of corporate and governmental technocracies as they would become, could in their day be counted as iconic of the age.

As early as the Balkan wars in the 1990s, but certainly with 9/11 and the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and now the civil wars and jihadist terror of ISIS enflaming the Arab World, the cyberpunk cinema was made to seem prophetic of the shift in warfare from national armies in declared battle to what broke down to a series of more contained, regional terror and guerrilla strikes by insurgents making due with technological scraps, volatile compounds and the primitive hijacking of a state's own commercial jets. (Shortly after writing this post, the AFP News reported that Ukrainian separatist forces broke into a museum in Donetsk commemorating the Second World War to make off with and a World War Two-era T-54 tank and two Howitzer artillery pieces to be used in combat.) The resources of rebels and jihadis in defiance of, and initially invisible to, the technocratic industrial-military complex and its intelligence satellites exploit the vulnerability of the goliath state with hundreds of little davids hidden away in sleeper cells. It is the stuff of science fiction come to life, only it possesses an ideological fervor unimagined by the screenwriters. Even before 9/11, the global obsession with the proliferation of ICBMs by superpowers was being supplanted by a resurgence and spread of comparatively primitive ground and guerilla warfare. And the element of faith that had been largely missing from international warfare for two centuries shocked the global audience into summoning to mind their own end-of-times scenarios. In short, realpolitiks seems to have caught up with the sci-fi and cyberpunk universe, at least in making its mythopoetic characters and institutions more relevant to our own identities and organizations. The mountain was literally brought to Mohammad, and it's name is Paramount.

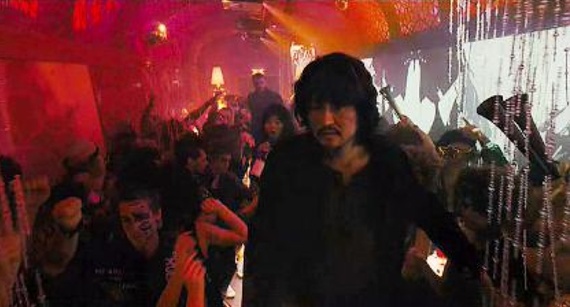

Enter Snowpiercer, which in its first minutes distinguishes itself from all prior dystopian visions in dwelling not on some plot to colonize or commercialize the planet, but solely on the injuries that homo sapiens self inflict in a tightly-controlled and perpetually-observed microcosm of the human condition. Even the violence is profoundly human in its motivating imperative for survival. Instead of gratuitously barraging us with any number of collaterally-damaged, faceless (or artificial) victims who die for no-identifiable cause, the camera surveys a recognizable humanity who die for the subsistence needs that the average working-class household struggles to procure. Albeit, it is a humanity so impoverished that most of us only find such despairing souls in homeless encampments. But it is the effect on the audience that counts, and here we are compelled from the start to react with greater empathy after seeing the prolonged hunger, cold, pain and disability that afflict the train's underclass. It helps that Snowpiercer's intent representation of all our paranoias and real misery alike are underscored by the film's evasion of easily-identifiable genres. It also helps that the setting of the train's rear cars isn't futuristic, save perhaps the doors joining one car to the next that bare the familiar design of hyperspace portals. It matters because though we know it is a sci-fi flick, upon acquaintance the rear cars take on the ambiance of a war film set in a gulag, or for theater enthusiasts, it may bare resemblance to a stage set for a Bertolt Brecht play, replete with Brechtian gallows humor surfacing throughout the production.

Combined with the film's broad, furious sweep of human cruelty and desperation--a combination that makes it a truly rare and authentic vehicle of moral and political, if potentially delusory and unstable, realpolitiks--the character portrayals effectively suspend our disbelief enough for us to find the onslaught of barbarism believable in ways that we are unable to in films such as The Matrix, which distances us with its stylizations and virtuality. All of which is a tribute to Snowpiercer's daring capacity to synthesize high-minded, avant-garde political allegory, off-key ironic black humor, and unrelentingly-brutal social conflict, in the wrapping of a summer entertainment.

Once the civil war begins, it becomes apparent that not since Sergei Eisenstein made Battleship Potemkin and October:Ten Days That Shook the World, and Fritz Lang made Metropolis, has a depiction of class struggle leading to violent revolution been so prominently placed in the foreground of a mainstream production. All of which makes Snowpiercer the more remarkable for Bong's setting of his final solution to class difference and the final revolution that meets it head on in an exceedingly long train shuttling the last few hundred remnant humans and other life-forms allowed to survive the freezing over of the earth.

Ordinarily, comparing a mainstream film to the masterpieces of world political theory would seem laughable. But sharpening the perspective presented us in Snowpiercer with its comparison to the centuries-old models elaborated by the three great political philosophers, Niccolo Machiavelli, Thomas Hobbes and Karl Marx helps us to see our world, if not ourselves, in broader, bolder strokes. The intent isn't to reduce the artistic and entertainment value of the film to academic schools of thought. It is to heighten our understanding of the degree of sophistication at work in the organization of imagery and concepts that expand mainstream expectations, and hopefully the demand for future productions of ever-increasing, yet enthralling, complexity. Science fiction has arguably done more to heighten the intelligence quotient of entertainment in film through the use of mainstream mythopoetics than any other modern popular genre. So rich is science fiction's mining and integration of disparate technological, political, social, cultural and popular mythological models, it can be argued that we have to go all the way back to the drama and comedy of the Greek golden age, or even to Homer, to find so voracious a capacity for assimilating the entire range of knowledge into an art of entertainment. All of which is to say that it is well time to heighten our standards for, and definition of, popular entertainment as art--at least when it applies, which is by no means often enough to satisfy the standards of high-capacity minds.

We needn't look far or deep to find the political models of Machiavelli, Hobbes and Marx at work in the film, what with the entire plot and picture consisting of a single, primitive and prolonged course of action against an oligarchy loyal to a single and mesmerizingly all-powerful, if invisible and mythic, figurehead. Despite the rebels' severe repression, hunger and physical handicaps (many are missing limbs), the makeshift, unarmed collective--a wretched and undisciplined lumpenproletariat little better off than slaves and prisoners--mobilizes with a single, agonizingly slow push forward to the front of the train. Proceeding cautiously from one locked car to the next, having to improvise a new force of entry for each thick metal door, they encounter a different and more maligning offensive with each breakthrough. But the effort is exhilarating as they feel a power course through them they haven't known in their seventeen years on the train, and the underclass gradually puts its idealism above their individual motives to become a single organism propelled by the common imperative to seize power.

This is the Marxist ideal realized in the film. But Marxist principles never fully take precedence even if the Marxist vision of class struggle intensifies, as the unseen but conservative and elite class awaiting at the train's front is set on maintaining their status quo--with the effect being one of the proverbial unstoppable force colliding with an immovable object. Even before the resulting bloody annihilation comes down to two opponents, we can see the conflict representing a binary model of naked competition, the operative identity of which is interchangeable among models--democracy against authoritarianism; the proletariat against the bourgeois; the terrorist against the army; the avant-garde against the status quo.

The eco-factor in Snowpiercer strategically anchors the story's relevance to the moment, despite that it is only through the long-winded exposition of characters and instantaneous flashes of memory that we learn of the botched attempt to stop global warming with chemical coolants ejected into the atmosphere. Both the lateness and the ineptness of the attempt to reverse global warming on face value implicates a Republican-like denial of, and profiteering off, climate change. It's an impression made stronger, given that the remedy to be released into the earth's atmosphere has destroyed all life on earth except those high-net worth individuals whose resources buy their board on the train and whatever life they deign will help sustain them.

And with the cataclysmic deep freeze of the continents and oceans into a single global glacier, what they deign to bring is the labor required for the perpetual journey, a manpower allowed to "gate crash" the train, so long as the "interlopers" proved themselves strong and resourceful enough to fight and kill their way aboard before the train door slammed shut and bolted. As the high-net-worth passengers in the distant and unseen front cars of the train became increasingly outfitted with aquariums and terrariums to maintain their aristocratic expectations of luxury, albeit now brought down to the scale of eating sushi and vegetables, the no-net worth underclass that crammed the train's tail has been envisioned with all the impoverished ferocity rendered by Victor Hugo and Charles Dickens during the Industrial Revolution. Except that the 19th-century authors never foresaw feeding their have nots with a cannibalism consuming children, the elderly, the disabled and--for those poor too lofty for the supreme degradation--the devouring of one's own limbs.

The wealth of such horrific scenes and accounts of the trains's history seals the materialist, Hobbesian world view of a mechanistic nature by which extreme deprivation draws out our animal instincts from beneath a social veneer shed under the excruciating circumstances of famine. While calling most easily to mind the many refugee camps that dot the developing world, for Americans the motif of famine atop a glacier (that Snowpiercer is named for) recalls such infamous accounts of 19th-century cannibalism demonically brought down on the John Frémont exploration expedition in 1842 and the westward emigration of the Donner Party in 1846--each stranded an entire winter in the Rocky Mountains and forced to choose between starving or consuming their dead. Bong, however, no doubt was more likely impelled by the recent accounts that have been leaking out of North Korea about the cannibalism that ensued when, in the mid-1990s, famine wiped out as much as ten percent of the population. And as a 2013 report in The Washington Post made clear, it is that most chilling reality of the easiest prey of cannibalism which makes famine so unspeakable, unthinkable--euphemistically put by reporter Max Fischer, "that children feared to sleep in the open". Whatever sources served Bong and his co-scripter, Kelly Masterson, or for that matter the creators of the French graphic novel, Le Transperceneige, which served as Bong's inspiration, the moral wealth that accompanies such accounts of infamy and heroism, as in Snowpiercer, derives entirely from learning which souls resorted to, or refused, devouring human flesh.

In their ghastly initiation to the Snowpiercer, the gate crashers, lumpenproletariat, disenfranchised--whatever term we choose to call those forced into the rear of the train--may have been better left dead, given that in the early days of their survival and forced isolation by the oligarchy at the front, their extinction was calculated, cannibalism and all. Once the population had sufficiently decreased at the train's tail, the elite class fed, and thereby won, the tentative allegiance of the disenfranchised survivors with a single daily meal made of an appallingly-black gelatinous protein bar extracted from mysterious origins. There is no need to account more, for there isn't a moment that we aren't made aware of the precarious class relations dependent entirely on how well the exploited labor and commodified bodies of the proletariat class perform. There is also a middle, security force class that, for whatever unseen benefit, is compelled to buffer and safeguard the train's high-net-worth population at the expense of the most impoverished.

If I here belabor the corollaries between the miseries seen in the film and those we know directly from life or through the media, it is because Snowpiercer reads onscreen as if it had foreseen the apologies offered by the mainstream critics for audiences not wishing to dwell on the politics and violence onscreen, as I have here. There is no reason we must enter the fray onscreen, the critics assure us. It's all an allegory we are told, without informing us to what such unrelenting ferocity and inhuman disfigurations are allegories of. It's yet another dystopia, goes the most blatant euphemism for fascist self-loathing externalized by the film's depiction and accounts of extermination. Chief among these apologies is the not-to-be-forgotten and commercially-imposed imperative that the film functions chiefly as entertainment--fun, as one critic reduces it--which is as much willful short shrift as anyone can expect from the corporately-employed media commentators whose collective mission is to fill theater seats and sell DVDs.

Whether we agree with or blame the mainstream critics' avoidance of the film's real-world correspondences, irony resonates in the critics' evasive silence and apologies by mirroring, if not fulfilling, Snowpiercer's depiction of the propagandists who dispense the manipulative disinformation issued to the train's underclass. Our critics may lack the over-the-top talent for parody faultlessly performed by Tilda Swinton, as the fascist Minister of Information churning out the grist of the train's propaganda machine, or that of Alison Pill as the kindergarten teacher instilling reverence in her young charges for the train's sacred "Eternal Engine" and its maker-made-savior and deity, Wilford--a clear swipe at the megalomania of Mao Tse-Tung and Joseph Stalin and the mass cult of reverence and deference that their exaltation as idols was calculated to effect among the populace. With certain of the mainstream critics duplicating the film's portrayal of societal controls, we find the truths of the drama spillover from the screen onto our reality through the critics' dispersion of half-truths.

Yet even without such a time-specific political and economic setting, Snowpiercer invites our projection of real historical contexts to elaborate what is no more nor less than an exceedingly graphic, if fittingly apocalyptic denouement to the history of human civilizations and tribes marked by unrelenting genocide and nihilism. As for anyone who thinks the film's script to be over the top, they need only consider that estimates now hold that seventy-million Chinese citizens were annihilated in Mao's Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution, while nearly sixty-two million Soviets and Germans were murdered by Stalin's Gulag State. Add to that staggering total, ten million noncombatants who were exterminated by Hitler's stormtroopers and camps. And then there are the more recent genocides of Cambodians by the Khmer Rouge; the Vietnamese killed by the Viet Cong; the slaughter of Tustis at the hands of the Hutus in Rawanda; the ethnic cleansing of Bosniaks, Croatians and Serbs in the Balkans, and the sustained starvation of North Korean peasants and Sudanese and Somali refugees.

There is no mistaking Snowpiercer's modeling of the total oligarchical domination that could expand the chokehold that such high net worthers have on the prosperity of entire societies and cultures, as witness the kind of market machinations that ushered in the 2008 recession and which still threaten to undermine the free trade and enterprise that only a decade ago promised to alleviate poverty, crime and disease everywhere on earth. More succinctly, if cosmologically put, Snowpiercer is a materialist and mechanistic destroyer of such idealistic notions as altruism, ethics, individualism, free will, equality and democracy.

If we can look forward to what interpretations more in-depth and informed cultural and academic commentaries will hoist onto Snowpiercer, it is because of what's missing so far in the mainstream critics' coverage of the film's undeniable focus on class struggle--both a discussion of the film's mythopoetic reflection on real-political divisions and ideologies at work in the world and, feasibly, it's effect as a morality tale intent on stimulating serious political debate and activism.

Marx's political and economic model is best represented onscreen in the portrayal of a forced exploitation degrading human relations to degrees of servility and slavery, the division of human beings that, though imposed by the combined requirements of survival, opportunity and resourceful ability, catalyze rebellion. In this regard, Snowpiercer opens at the end of the last stage of class conflict that Marx and Friedrich Engels foresaw necessitating cyclical revolutions, and which we learn late into the film, had recurred repeatedly onboard the train over the course of seventeen years.

On the surface, it appears that Bong follows Karl Marx's dialectical view of historical revolutions in keeping the division of interests strictly binary--a simple equation of the oppressor to the oppressed--with a buffer of security forces entrusted to the middle cars of the train as a small but well-armed shield-and-assault squadron that can only have been procured from the mercenary personalities within the train's rear. But while the equation of interests and differences on the surface appear to keep to the model of labor to capital, and proletariat to bourgeoise that Marx advanced, we know from the events that brought on the decline of 20th-century communist revolutions that such an exclusively binary and dialectical model is an illusory condition imposed ideologically onto human nature and the structure of societies. The flaw in Marx's theory is that revolutions cannot be confined only to two classes for any significant duration, which is why the dictatorship of the proletariat could never confine itself to one set of interests, what with the communist societies, like all other societies, being naturally inclined to fracture along several ideologically individual and divisive cultural veins.

It is only the staging of a physically cramped, exceedingly long and narrow battlefield within the Snowpiercer train--a space that allows camera room for only two antagonistic forces--that both invites and imposes the equation of a binary, Marxist class struggle at work. In the real, multi-dimensional world of nations, there isn't only two collective antagonists competing against one another, but any number of conflicting parties in competition to realize their unique interests, a conflict coming from all directions that better fits the model of society that Thomas Hobbes describes in Leviathan, and which undermines Marx's dialectical relations on the train as in the real world of economies and states. We also learn that all the rebels are not what they seem, further supporting Hobbes' principle of "every man against every man". Anyone who reads of Hobbes's bleak mechanism of nature is likely to see how Snowpiercer acts out a model of the perennial civil war of homo sapiens divided by natural predisposition. But Machiavelli also comes to mind as we watch Snowpiercer's more gullible and power-struck followers on both sides show themselves to be mesmerized and roused by leaders who look to violence and brutal suppression to achieve their aims, whether they have the support of the mob or buttress their supremacy with cruelty and annihilation. Such allusions to the open seizure of power, especially among the oligarchy, easily fits at least two of the more ruthless princely profiles that Niccolo Machiavelli paints as the "usurpers" and "mobilizers" of the warring Italian states he wrote about during the Renaissance.

(SPOILER ALERT: For maximum suspense, read the remaining commentary only after seeing the film.)

Although the rebellion starts out with the rebels' agonizingly slow, car-by-car, occupation of the train, it is only well after they reach the front, where the oligarchy live, shop and play, that we learn the deadly consequences of the rebels' actions has not only been anticipated, but instigated and manipulated to fulfill one man's mechanistic world view. It is at the film's climax that we find the most singular and extreme Machiavellian mandate commanding our attention. And that is a rationalization for all the strife and executions, even the cannibalism in the early years of the train--all of which, we are told are required to maintain the balance of the train's ecosystem--really a technosystem ingeniously designed by Wilford, the entrepreneur and engineer who made the train. Played by Ed Harris in the image of one of Machiavelli's maniacally ruthless princes, Wilford believes himself to be benevolent and wise, as if he has read Machiavelli's praise for the prince that balances "all those injuries which it is necessary for him to inflict" with those "benefits given little by little, so that the flavor of them may last longer". The feudalistic reasoning that Wilford offers for the necessitation of his war is meant to strike modern audiences as inhuman and demonic. In fact it is representative of an authoritarian logic inducted by regimes wherever democracy or a benevolent ruler has been crushed. I refer to the so-called imperative of imposed population control and healthful living space that in times and places of overcrowding manifests in the imposition of arbitrary death sentences, the one-child policy of China, the soldiering of suicide invasions, even in some cultures the offering of human sacrifice to blood-thirsty deities.

We learn of the rational for genocide as the two adversarial leaders become acquainted in a truce over a meal--call it a last supper, fittingly of meat, the first time in seventeen years for Curtis, a daily dish for the god. Over the absurd cordiality of the meal, the image of gentility that has masked so many of history's atrocities, we hear Wilford's rationalization of genocide premised on the dire need for living space--the Lebensraum that Hitler re-introduces in Mein Kampf and sold to the economically strapped and overcrowded German citizenry of the 1920s and 1930s. But then living space is also the modern variation on the ancient urgency of procuring territories to justify war and the perpetuation of the race. Given that the overcrowding that comes with population growth rose exponentially in the last century, we no longer associate the term exclusively to the Nazis or the imperialist Germans and Prussians before them. In fact, just last month, Israeli Likud Deputy Knesset Speaker, Moshe Feiglin, justified emptying Gaza of its Palestinian residents when he writes that Gaza "will become part of sovereign Israel and will be populated by Jews. This will also serve to ease the housing crisis in Israel." In all fairness, I must immediately add that living space is equally the interest of Hamas, however little they can do about it at present.

In Snowpiercer, such rationalizations are proudly accounted for by Wilford as a stroke of genius--his own--as we listen to his maniacal variation on Darwin's natural selection unfold, one that manifests both in the animal food chain and the survival of the fittest evolutionary principle combined and served up in a particularly delusional, if dramatically enthralling and largely one-way conversation between the film's leading antagonists. We met the rebel leader Curtis, lent a shade of reticence and cluelessness by Chris Evans, at the beginning of the film, and it is his mythopoetic character arc as a Prometheus figure (not unlike an Occupy protestor) who, like his Greek prototype, introduces fire to the train's underclass for its defense.

With all its cold calculation of class genocide, it matters that Bong took pains to racially diversify the principal cast, among whom the peoples of all continents are ostensibly represented by color. It is revealing, however, that the first-class compartments of the train, secured with impenetrable doors and several cars outfitted with industrial, agricultural, and aquatic installations that simultaneously sustain and entertain the train's oligarchical class, largely appear to be whites who have absconded with the young of all the poorer races sequestered to the rear. Although saved from the cannibalism from which so many other children perished, they are then either indoctrinated in the pedagogy of propaganda or enslaved in the cramped bowels of the train to facilitate locomotion.

If the horrors of Bong's revolution appear truer to Hobbes' paranoid vision of the mechanistically-inborn imperative suffering all humans to savage competition than to Marx's organized rebellion, it is no doubt because even the most successful revolutions, whether waged in democratic liberty or in the name of Marx's dictatorship of the proletariat, have devolved into dictatorships against the earlier inhabitants, classes and rulers--and in Communism's case, against the very proletariat it was supposed to liberate. It may be likely that Snowpiercer has been influenced both negatively and positively by the French Revolution, that took over a century to dispense wider democratic liberties without the persecution of one class by another; or by the American Revolution, whose humanism was thwarted flagrantly by the genocides and evictions imposed on Native Americans and the enslavement of Africans.

To my knowledge, neither Bong nor his co-scripter Kelly Masterson, nor Jacques Lob, Benjamin Legrand and Jean-Marc Rochette--the creators of the graphic novel, Le Transperceneige, have made statements invoking the formidable trimurti of Machiavelli, Hobbes and Marx as inspiration. On the other hand, Bong as a South Korean can only be intimately familiar with the Marxist, Machiavellian and Hobbesian machinations of the father and son supreme leaders of North Korea, the late Kim Jong-il and his successor, Kim Jong-un. As for the rest of us, even our most populist attitudes toward modern equations of power, class and conflict are shaped by what has been disseminated into the mainstream by Machiavelli, Hobbes and Marx--and at no time more virulently than when a resurgence of protests, and any one of the protracted crises of joblessness, homelessness, and military interventions marking the last decade, punch a hole through our prosperity charts and peace treaties.

No one has since surpassed Machiavelli, Hobbes and Marx in the analysis of cruelty, repression and extreme degradation, and calling them to mind, as Snowpiercer does in the universal language of actions onscreen, enriches our interpretation of several scenes throughout the film. But that shouldn't stop the viewer from pulling out his or her favorite political theorist (say, Judith Butler on the 2014 Gaza debate, or better yet, to speculate creatively and critically on the film's iconography and rationale.

Finally, the most salient distinction in the ratio between Snowpiercer's entertainment value and its moral value is that, whereas all the other dystopian films before it bring some semblance of moral superiority, if not political victory, for all their heroes' striving, it is nihilism that consumes both sides of the Snowpiercer equation with disregard for such human values as valor and righteousness. The only operating principle, if a principle is what it can be called, is the end that complete entropy allows.

And yet even in that end a new Adam and Eve revive hope in the longevity of the human race. But to anyone who is an avid viewer of the Alien films recognizes the lesson that the survivors left to repopulate a world can become as rapacious an organism at odds with all other life forms in its path.

It is likely that if we of the post 9/11 era had a masterful war film, or a film portraying the atrocities of our time matching such films as The Killing Fields, Hotel Rawanda, The Battle of Algiers, and the scores of Holocaust productions, we would be bestowed a more potent vehicle of catharsis for the historical recollections of real genocidal pathology still to be endured by survivors of the 9/ll strikes and the wars that ensued and continue so many years later. On the other hand, such films don't in general strive to embody the Hobbesian politics of the human condition that can be universally seen to apply to the most horrific brutalities while courting the viewers' projections of personal experience. For specific wars and genocides as those narrated in the films just mentioned are treated by the modern international community as aberrations, when in fact history gives every indication that ethnic cleansings haven't been the exception but until recent centuries were the rule of the majority of hostile relations between civilizations, states and tribes. Neither do the historical genocide and war films by any internal logic necessitate existentialist visions of the imperative to rise up in rebellion to face the fascisms imposed by the Left or the Right. Bong, by contrast, has provided us with the particularly chilling allegory of our new millennium, where Left and Right become near impossible to distinguish when either can assume authoritarian controls while ravaging their own class.

If we here neglect the impact of John Locke's Social Contract, or the Enlightenment principles of Rousseau, Adams and Jefferson, it is because Snowpiercer doesn't so much as unconsciously slip in analogies to such world-altering documents as the Magna Carta or the U.S. Constitution. Like Marx's trampled proletariat or Machiavelli's and Hobbes' mob forced to submit to basic survival skills and strategies of violent takeover, there is no time or room to consider a negotiation of consents, even if the imperious and largely-invisible Wilford were inclined to entertain them. And if the film promotes a predominantly Hobbesian view of human nature as a compulsive competition for survival and self-interested power, it is also without a model of heroism. For heroism can only proceed from unselfish choice and responsibility to others--sentiments that mechanistic systems of survival faced with pending extinction at any moment disallows. Whether we see the brutality that dominates the action sequences to be the stuff of Hobbesian and Machiavellian self-interest, or the Marxist imperative of putting the collective will first, such extreme visions and accounts of mayhem and sadism reduces even the past achievements of civilizations to an irrelevant contingency that at any catastrophic moment can revert to the mechanistic stimulus and response at work in all involuntary body functions. As such, the efforts of Curtis (who admits his participation in the train's early cannibalism) and his comrades in waging rebellion can only be contextualized as our animalistic imperative for survival. That is, until a new peace and prosperity may allow for reflective and renewed sentiments--but that is a huge contingency on a planet become a sterile glacier.

The following excerpts from the writings of Machiavelli, Hobbes and Marx are supplied only for an informative comparison with the film, Snowpiercer, and are not intended to promote ideology of any kind. The spellings remain as they were found, and in the case of Hobbes, as they were originally published.

.

...having led an enormous army, composed of many various races of men, to fight in foreign lands, no dissensions arose either among them or against the prince, whether in his bad or in his good fortune. This arose from nothing else than his inhuman cruelty, which, with his boundless valour, made him revered and terrible in the sight of his soldiers, but without that cruelty, his other virtues were not sufficient to produce this effect.

Niccolò Machiavelli, The Prince, 1531

In seizing a state, the usurper ought to examine closely into all those injuries which it is necessary for him to inflict, and to do them all at one stroke so as not to have to repeat them daily; and thus by not unsettling men he will be able to reassure them, and win them to himself by benefits ... For injuries ought to be done all at one time, so that, being tasted less, they offend less; benefits ought to be given little by little, so that the flavour of them may last longer.

Niccolò Machiavelli, The Prince, 1531

Whatsoever therefore is consequent to a time of Warre, where every man is Enemy to every man; the same is consequent to the time, wherein men live without other security, than what their own strength, and their own invention shall furnish them withall. In such condition, there is no place for Industry; because the fruit thereof is uncertain; and consequently no Culture of the Earth; no Navigation, nor use of the commodities that may be imported by Sea; no commodious Building; no Instruments of moving, and removing such things as require much force; no Knowledge of the face of the Earth; no account of Time; no Arts; no Letters; no Society; and which is worst of all, continuall feare, and danger of violent death; And the life of man, solitary, poore, nasty, brutish, and short.

Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, 1651

To this warre of every man against every man, this also is consequent; that nothing can be Unjust. The notions of Right and Wrong, Justice and Injustice have there no place. Where there is no common Power, there is no Law: where no Law, no Injustice. Force, and Fraud, are in warre the two Cardinall vertues. Justice, and Injustice are none of the Faculties neither of the Body, nor Mind. ... It is consequent also to the same condition, that there be no Propriety, no Dominion, no Mine and Thine distinct; but onely that to be every mans that he can get; and for so long, as he can keep it. And thus much for the ill condition, which man by meer Nature is actually placed in; though with a possibility to come out of it, consisting partly in the Passions, partly in his Reason.

Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, 1651

The history of all hitherto existing societies is the history of class struggles. Freeman and slave, patrician and plebeian, lord and serf, guild-master and journeyman, in a word, oppressor and oppressed, stood in constant opposition to one another, carried on an uninterrupted, now hidden, now open fight, a fight that each time ended, either in a revolutionary re-constitution of society at large, or in the common ruin of the contending classes.

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, Communist Manifesto, 1848

It is enough to mention the commercial crises that by their periodical return put on its trial, each time more threateningly, the existence of the entire bourgeois society. In these crises a great part not only of the existing products, but also of the previously created productive forces, are periodically destroyed. In these crises there breaks out an epidemic that, in all earlier epochs, would have seemed an absurdity--the epidemic of over-production. Society suddenly finds itself put back into a state of momentary barbarism; it appears as if a famine, a universal war of devastation had cut off the supply of every means of subsistence; industry and commerce seem to be destroyed; and why? Because there is too much civilisation, too much means of subsistence, too much industry, too much commerce.

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, Communist Manifesto, 1848

-- This post was altered on 8/25/14 with mention of the Donetsk Museum break in by Ukrainian Rebels and the addition of ISIS to the jihadis named.

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.

Follow G. Roger Denson on Facebook.