Sarajevo begins to heal from its haunted history

If you dare to visit here — and I’m glad I did — you’ll eventually stand beneath the elegant geometry of Gazi Husrev-bey Mosque (built in 1530) or sip a beer at the Sarajevo Brewery (founded in 1864) or tiptoe atop the stone walls of the White Fortress, staring out at a 300-degree panorama of mountain slopes, red-tiled roofs, soaring minarets and far too many cemeteries.

But first, you’ll probably go where I went first: a short, low-slung bridge that doesn’t look a bit special.

That’s the Latin Bridge. And on June 28, 1914, it lay along the route of the Austro-Hungarian Empire’s Archduke Franz Ferdinand, who was visiting with his wife, Sophie, the duchess of Hohenberg.

As they well knew, Sarajevo has been a cultural crossroads since the 16th century, its mosques and synagogues neighbored by Orthodox and Catholic churches — the Jerusalem of Europe, some said. But the Balkans were never particularly peaceful, and on that day in 1914, the region was ripe for trouble.

The royal couple had already survived a botched bombing attempt that morning. And then, as their open car idled near the bridge, outside the Moritz Schiller delicatessen, a 19-year-old Bosnian Serb named Gavrilo Princip stepped up with a pistol and shot them dead.

His idea was to help neighboring Serbia gain territory. Instead, as is told in the museum where Schiller stood, he started World War I.

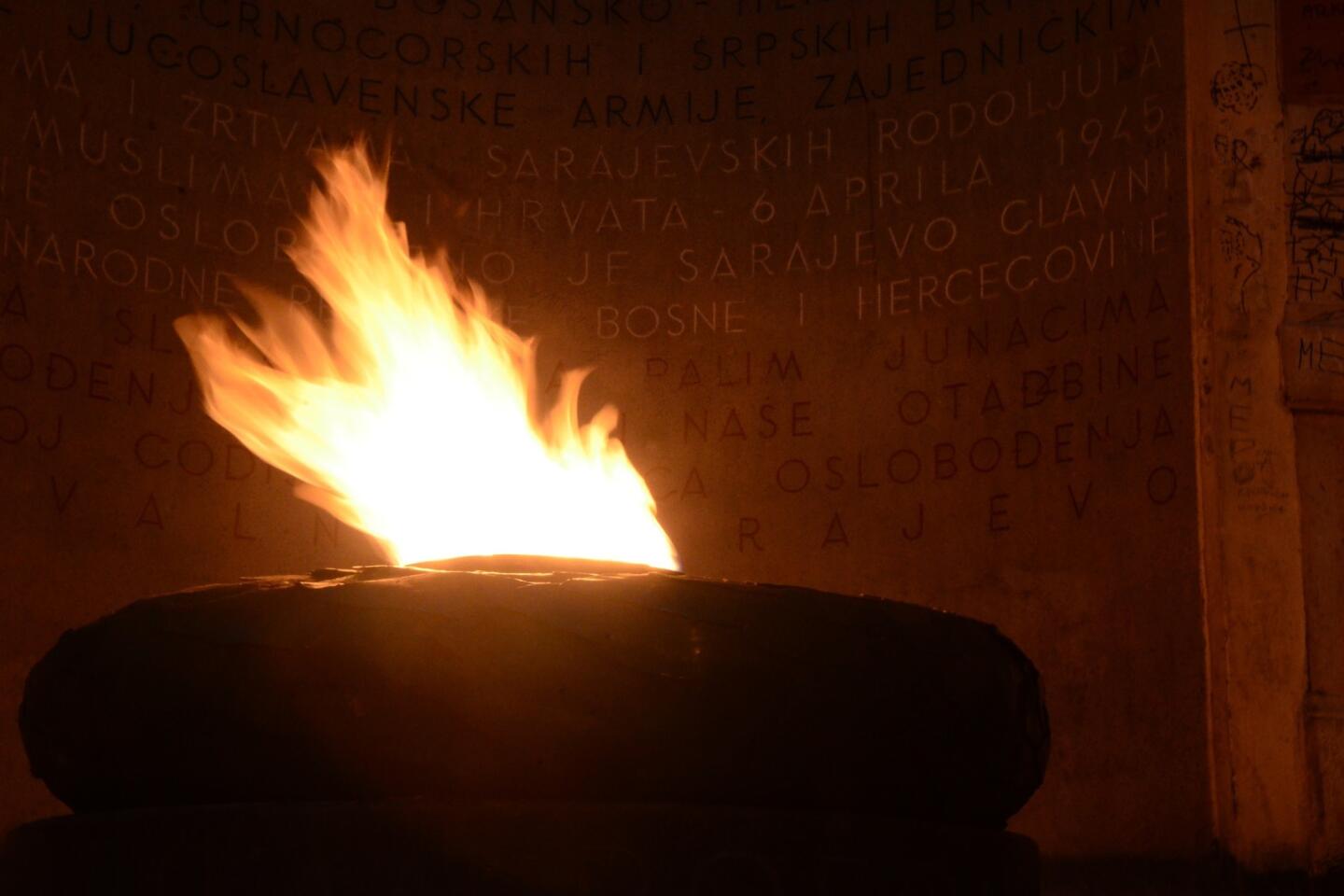

I reached Sarajevo in April, nearly 100 years after the assassination and just 22 years after Bosnian Serb troops seized the high ground that surrounds the city and started shooting. They killed about 11,000 people in 44 months, the longest siege in Europe since World War II. But many endured, much has been rebuilt and visitors get a hearty welcome.

Now a newcomer can head for a $50 lavish dinner at the Four Rooms of Mrs. Safija (4 Sobe Gospodje Safije, opened in 2008) or spend $100 for a simple bed at the Hotel Kovaci, which also opened in 2008. Or you can sit by the fountain in Bascarsija, the oldest neighborhood, and join the children feeding corn kernels to the pigeons.

Old guys play chess in the park with foot-high pieces. Young guys break-dance along the pedestrian promenade. I felt safe at all hours. And as European capitals go, it’s cheap.

But Sarajevo (population an estimated 369,000) is far from easy. As local journalist and guide Amir Telibecirovic warned me on arrival, pedestrians travel on well-worn paths because many land mines remain on the city’s fringes. The record rains and floods in May probably made that worse.

“We have a saying: We have more history than we can stand,” said Telibecirovic, 41, who lost three family members in the siege.

International tourist arrivals, still well south of a million, have tripled since 2004. The Hotel Europe, the ritziest lodging in the city’s core, had a major renovation in 2009. In the business district, a stylish new Colors Inn opened in December. Near the former Holiday Inn where war correspondents holed up a generation ago, bold new commercial buildings rise.

In the House of Spite — a restaurant named for a 19th century real estate transaction — I sampled cevapi, or minced meat. At Cajdzinica Dzirlo teahouse, I tried salep, a creamy drink made with orchid roots, and compared notes with half a dozen young travelers from the U.S., Australia and Canada.

“Great people,” co-owner Diana Dzirlo told me. “And I always steal something from them — their energy.”

Sarajevo’s demographics are a sort-of mystery: Even lifelong Sarajevans often can’t tell at first glance who is Muslim, Serbian or Croatian, and numbers from a long-awaited census are due any day. But by a 1991 count, the city was 49% Bosnian Muslim, 30% Bosnian Serb (typically Orthodox) and 7% Bosnian Croat (typically Catholic).

With Telibecirovic guiding and translating, I toured several churches, mosques and a former synagogue, now a Jewish museum. We also circled the neo-Moorish national library, built in 1896, destroyed in 1992 and famously lamented by a local cellist who played in its ruins. It’s been gorgeously rebuilt (with help from international donations), and it officially reopened two weeks after my visit.

But there’s still plenty to worry about. Unemployment is officially about 40% (though that overlooks under-the-table jobs). Budget troubles have closed the Bosnia and Herzegovina National Museum since 2012. So many abandoned dogs prowl the city that an English charity, Dogs Trust, has stepped up to neuter and tag thousands of them since 2012.

Along Ulica Zmaja od Bosne, a.k.a. Sniper Alley, dozens of buildings are still pocked with scars from mortar fire, and some windows are still covered by paper that international aid workers were handing out 20 years ago.

But Sarajevans know plenty about making do and about smiling in the face of trouble.

Along an ancient alley in the old town, craftsmen recycle brass artillery shell cartridges into souvenir pens. By the airport, the secret passage that served as a resupply line during the siege is now the popular Tunnel Museum.

At Insider City Tours, the most popular offering is the “Times of Misfortune” itinerary. And at the Avlija restaurant, servers mark reserved tables with signs saying “Minirano” — the same word used to warn of mines in the countryside.

I was at Café Divan on my last morning in town, thinking about those signs, when Edin and Demir, a pair of students from the Muslim theological school down the block, leaned over to greet me and offer tips on sweetening my Bosnian coffee. They also had questions about America.

“For us, it’s strange to imagine a place where you can’t hear the muezzin,” Demir said.

For me, it was bracing to find such warmth and vigor in a city that’s seen such trouble.

By the way, when you do get to Sarajevo, look downstream from the Latin Bridge a few hundred yards and you’ll see a newer, sleeker span, designed by students Adnan Alagic, Bojan Kanlic and Amila Hrustic at the Academy of Fine Arts, built in 2012.

The locals call it the twisted bridge because it does a loop-the-loop over the river. You can’t look at it without smiling. If any place deserves a bridge like that, it’s Sarajevo.

Twitter: @mrcsreynolds

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.