Shortly before noon on a hot, blue-skied Sunday morning in July 1914, a white sail floated out from behind Lambay Island and began to nonchalantly make its way towards the small port of Howth, writes historian Turtle Bunbury.

Asgard was on the home straight from one of the most daring gunrunning missions in modern history.

At the helm was Erskine Childers, the best-selling spy novelist of the day.

Over the previous three weeks, he had skippered the two-masted yacht out to meet a German tugboat in the North Sea from which he received a cargo of 900 Mauser rifles and 29,000 rounds of ammunition.

The weapons were destined for the hands of the Irish Volunteers who had pledged to defend Home Rule for Ireland.

The importance of this iconic vessel’s role in shaping Irish history is considerable. Its cargo was to play a pivotal role in arming the rebels of 1916.

Read: Prof FX Martin's introduction to 'The Howth Gun-Running and the Kilcoole Gun-Running'

Less than a week after Childers sailed Asgard home with his extraordinary cargo, the planet had tumbled into the abyss of the First World War. It is inconceivable that the Asgard’s mission could have succeeded under those new circumstances.

And if Asgard had not made it back to Ireland, then the Irish Volunteers would have had precious few guns to hand when it came to launching their bid for an Irish Republic just 20 months later in Easter 1916.

The landing of Asgard also highlights the enormous and often overlooked role in which many leading members of the Anglo-Irish aristocracy and landed gentry played in igniting the flames of Irish independence.

Asgard, an elegant 50-foot gaff ketch, was built in 1905 by the designer Colin Archer, the son of a Scots couple who emigrated to Norway in the 1820s.

As a youth, Archer had spent several years in Australia before returning to southern Norway to establish a shipbuilding yard at Larvik.

He quickly became recognised as one of the world’s finest naval architects.

Amongst his best known boats was Fram, a ship that went on numerous expeditions to both the Arctic and Antarctic under men like Roald Amundsen.

Named for an Old Norse word meaning “Home of the Gods”, Asgard cost £1,000 (more than £84,000 today) to build, a fee paid by Dr Hamilton Osgood, a prominent Boston physician credited with introducing the first rabies antibodies to the USA.

He was a direct descendant of one of America’s oldest families; his ancestors had been on board the Mayflower.

Dr Osgood and his wife, Margaret Cushing Osgood, commissioned the yacht as a wedding present for their daughter Molly.

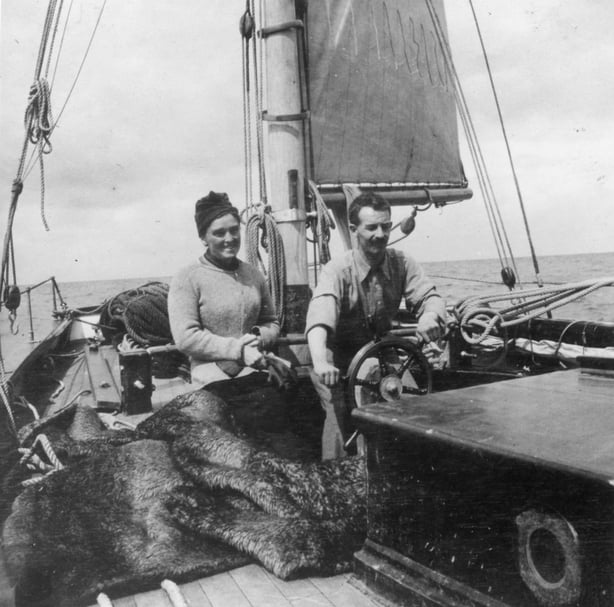

Molly and Erskine Childers on the Asgard, Picture courtesy of the Board of Trinity College Dublin

Archer’s yard was instructed to custom-build the vessel to the specifications of Molly’s new husband, an unusual Anglo-Irish writer called Erskine Childers.

Born in London in 1870, Childers was the son of an English professor of Oriental languages and his wife, one of the Bartons of Glendalough House, Co Wicklow, and a kinsman of the vineyard-toting family who owned Straffan House, now the K-Club.

Childers was just six years old when his parents succumbed to tuberculosis – his father died immediately and his mother, to whom he was devoted, was packed off to a sanatorium, never to be seen again.

Together with his four siblings and his Barton cousins, he spent the remainder of his childhood in the care of an uncle and aunt, secreted amid the lush 15,000 acre Glendalough estate.

His formative years were typical of his class. He went from an English public school to Cambridge to a desk job at Westminster.

Full of jingoistic zest, he joined the British Army in 1899 and marched off to South Africa to clobber the dastardly Boers.

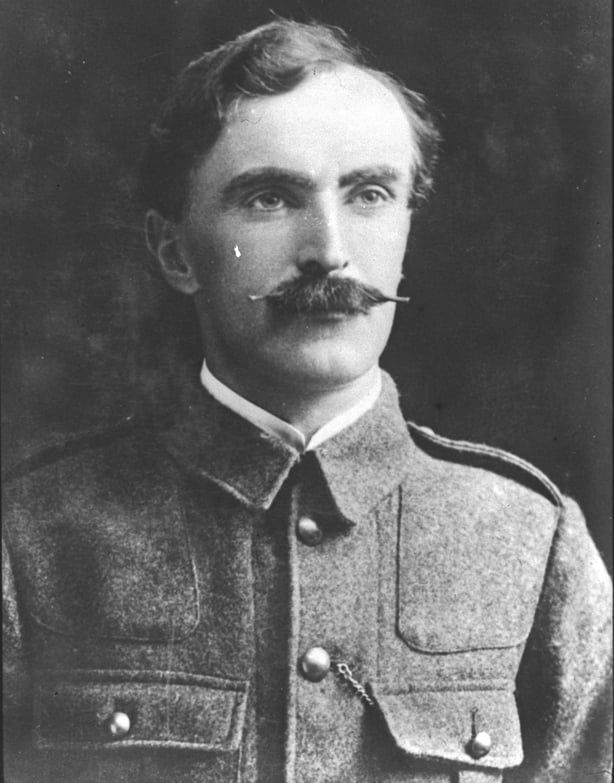

Erskine Childers in his British Army uniform in 1895

And then he started to change.

His experiences of the Boer War - of villages in flames, of women and children incarcerated in disease-riddled concentration camps – led him to seriously question the merits of British imperialism.

Erskine’s passion had always been sailing. During his 20s, he and his brother enjoyed yachting around the rocky coastline of the North Sea, keeping an eye on Germany’s ever-growing naval might.

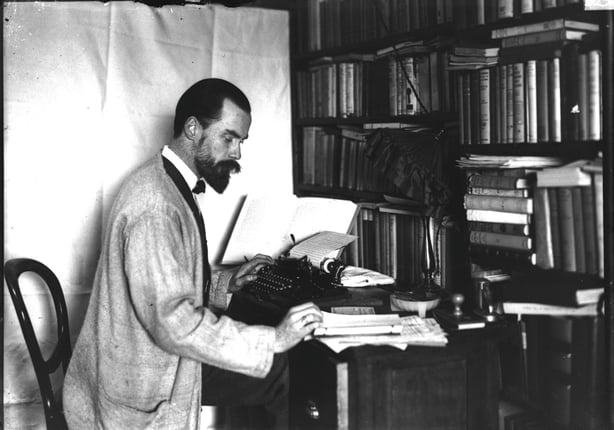

In 1903, he converted his knowledge into a best-selling thriller, “The Riddle of the Sands”, which, hailed as the first spy novel, made Childers a household name.

Shortly after “The Riddle” was published, Erskine attended a dinner party in Boston where he met and duly fell in love with Molly Osgood.

Molly had fractured both hips as a child and spent twelve years on her back. She was obliged to use two canes to support herself for the remainder of her life.

Despite this disability, she shared Erskine’s passion for the sea and was an accomplished helmsman. (Pic courtesy of the Board of Trinity College Dublin).

Despite this disability, she shared Erskine’s passion for the sea and was an accomplished helmsman. (Pic courtesy of the Board of Trinity College Dublin).

The couple were married in 1904. His cousin Robert Barton stood as Best Man. And they scored Asgard as a wedding present.

The newlyweds then settled in London where their first son, Erskine Hamilton Childers, a future President of Ireland, was born in 1905.

Their social life was low-key and involved much sailing around the North Sea and the Baltic on Asgard.

In 1908, Erskine joined his cousin Robert Barton and Horace Plunkett on a motor tour of southern Ireland.

The experience convinced the cousins that colonialism was fundamentally wrong and they became open supporters of Home Rule and, from 1913, of the Irish Volunteers.

In April 1914, the Childers learned that Sir Edward Carson’s Ulster Volunteers (who were utterly opposed to Home Rule) had successfully landed a shipment of 35,000 German rifles at Larne.

The British authorities had seemingly watched the whole thing unfurl and done nothing to intervene.

Appalled by this sudden imbalance of strength in Ulster’s favour, Erskine and Molly joined a committee of well-to-do Republican sympathisers who began to look at ways of arming the Irish Volunteers in a like manner.

As Padraig Pearse reputedly remarked, “the only thing more ridiculous than an Ulsterman with a rifle is a Nationalist without one”.

The group met at the London home of the Co Meath born historian Alice Stopford Green and included Sir Roger Casement, Lord Ashbourne, Sir Alec Lawrence (of the Lucknow branch), Lady Young and GF Berkeley, a descendent of Bishop George Berkeley.

£1,524 was raised and a plan hatched.

Darrell Figgis was involved in negotiating the gun purchase (Pic: RTÉ Stills Library)

On 28 May 1914, Childers and the political activist Darrell Figgis, of the bookselling family, negotiated the purchase of 1,500 single-shot Mauser rifles (designed in 1871 and known afterwards as Howth Mausers) and 49,000 rounds of black powder ammunition from Hamburg-based munitions firm of Moritz Magnus der Jungere.

Yes, they were bargain basement guns but they were nonetheless reasonably efficient as the Sherwood Forresters would discover to their cost at Mount Street Bridge over Easter 1916.

Now to get them home.

The British authorities had fully anticipated such an arms shipment and were ready and waiting.

However, they hadn’t banked on Childers’ ability to spin a web of deceit right into the heart of British intelligence.

False reports convinced the British that, while a shipment was en route, it was being transported by an Irish fishing trawler.

And so, while the Royal Navy began intercepting all such trawlers, Asgard sailed out from Conway on the Welsh coast on 3 July.

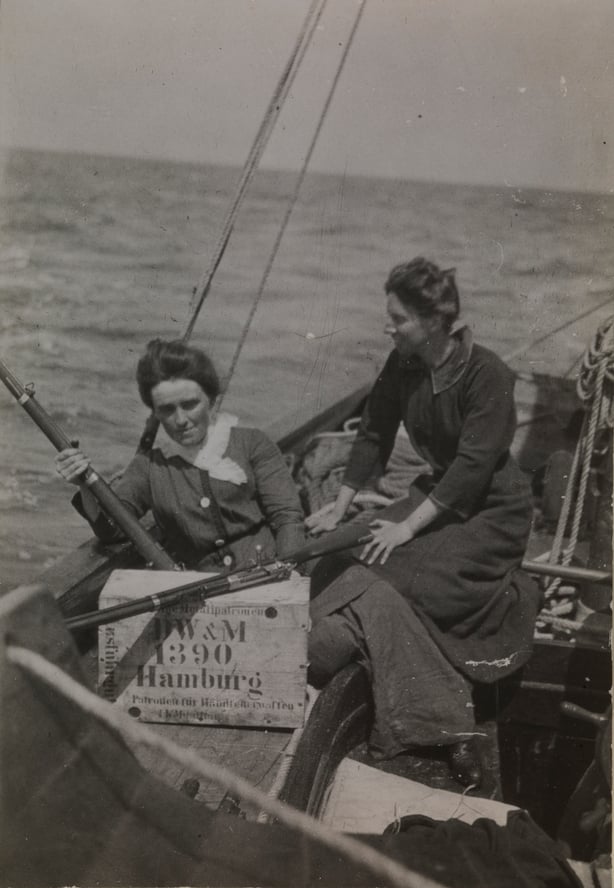

Molly Childers and Mary Spring Rice, courtesy of the Board of Trinity College Dublin

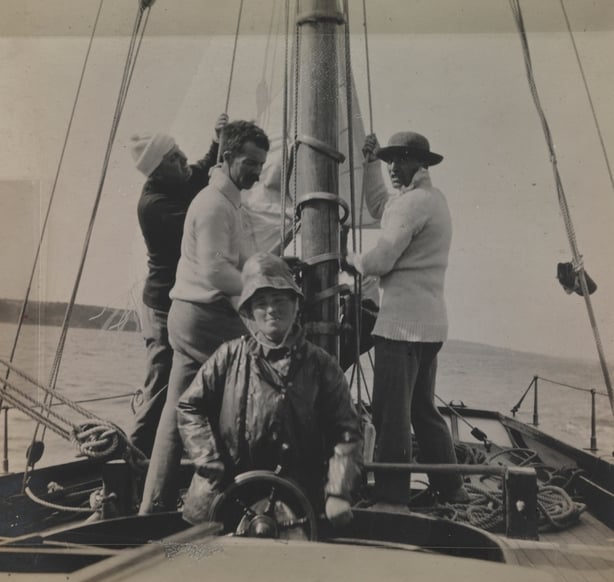

On board the yacht were Erskine, Molly, Mary Spring-Rice (a cousin of the British Ambassador in Washington), a British aviator and two Donegal fishermen.

And close at hand was a second yacht, Kelpie, a 26 ton ketch, built in 1871. Mary Spring-Rice’s Limerick cousin Conor O'Brien was at the helm, along with his sister Kitty O’Brien, a young barrister called Diarmuid Coffey (whose daughter Darina reminded me of the tale of the neglected Kelpie the same weekend this article ran in the Irish Daily Mail) and two paid hands, Tom Fitzsimons and George Cahill.

Nine days later, the two yachts rendezvoused with the German tug-boat Gladiator just off the Belgian coast, at the Roetigen Lightship at the mouth of the Scheldt River.

Gladiator duly unloaded its cargo and about-turned for Hamburg. (Pictures courtesy of The Board of Trinity College Dublin)

Gladiator duly unloaded its cargo and about-turned for Hamburg. (Pictures courtesy of The Board of Trinity College Dublin)

Kelpie was first to arrive and slipped away with the smaller part of the shipment (600 Mausers and 20,000 rounds) just as Asgard arrived.

It took five hours for the guns and ammunition to be loaded onto Asgard, as the rifles had to be unpacked from canvas bases and straw before being loaded onto the yacht.

Asgard steered her way home through a near fatal storm, a naval review in Spithead and a brief encounter with the British warship HMS Froward.

And on 26 July, she rolled out from Lambay Island, arriving into Howth Harbour at 12.45pm.

Standing in neat formation along the pier were 800 members of the Irish Volunteers and Na Fianna Éireann, headed up by Bulmer Hobson and The O'Rahilly.

The party was well prepared to receive the haul. Shortly before Asgard hove into view, phone-lines were cut and a Fianna trek-cart was emptied of its 150 oak batons.

Lookouts were stationed at every coastguard and police station in the vicinity. And the Volunteer officers were informed that one of the reasons they had been parading their men back and forth so much over the past few weeks was so that it wouldn’t look remotely suspicious when, say, a handsome two-masted yacht landed alongside them in broad daylight with a cargo of 900 Mausers and 29,000 rounds of ammunition.

As Molly Childers disembarked, The O'Rahilly gallantly kissed her hand, saying “You're the greatest soldier here, Ma'am, indeed ye are”.

According to The O’Rahilly, it did not take long to redistribute the cargo.

Michael Josephy O'Rahilly, known as 'The O'Rahilly', was a founding member of the Irish Volunteers (Pic: RTÉ Stills Library)

“Twenty minutes sufficed to discharge her cargo as many motor-cars flew with the ammunition to prearranged caches. And, for the first time in a century, 1,000 Irishmen with guns on their shoulders marched on Dublin town.”

When the authorities in Dublin Castle became aware of the Howth landings, they immediately dispatched a force of the Dublin Metropolitan Police to disarm the Volunteers.

When the authorities in Dublin Castle became aware of the Howth landings, they immediately dispatched a force of the Dublin Metropolitan Police to disarm the Volunteers.

After a small skirmish on the Howth Road, the police secured an ineffectual haul of 19 guns.

During the ensuing parlay, Bulmer Hobson issued a discreet command for the Volunteers to disperse from the rear, with their guns, as quickly as possible.

The Volunteers dissolved into the fields and by-ways; the guns and ammunition boxes vanished into thatched roofs and drainpipes, hedges and holes.

The day was to end on an ominous note when, in the wake of the landing, a detachment from the King’s Own Scottish Borderers opened fire on an angry crowd who were pelting them with rotten fruit on Bachelor’s Walk, leaving three civilians dead and 32 wounded, including young Luke Kelly, the father and namesake of The Dubliners singer.

News of Asgard’s heroic landing and the “Bachelor’s Walk massacre” spread like wildfire through the country.

Many feared a full-blown war with the Ulster Volunteers was imminent, not least when the remainder of the German armaments landed at Kilcoole, Co Wicklow, on 1 August.

Kelpie had been relieved of its load by the engine-powered Chotah, skippered by Sir Thomas Myles, a former President of the Royal College of Surgeons, who sailed out with Trinity-educated barrister James Meredith.

Hampered by a split in her main sail off the coast of Wales, Chotah reached the Kish Bank off the coast of Dublin on 1 August, nearly a week after the Howth landing.

That evening, Eoin MacNeill, the Howth-based founder of the Irish Volunteers, dispatched a 35-foot fishing boat called The Nugget out to meet it.

The fishing boat was crewed by the McLoughlin brothers and Michael Moore, and included some of MacNeill's men.

They successfully transferred the weapons to The Nugget which took them on to Kilcoole Strand, Co Wicklow, where the consignment was landed, shortly before dawn.

The greeting party included Cathal Brugha and future President Sean T O'Kelly. The Nugget then innocently went out for a day's fishing before returning to Howth.

Three days later, Britain declared war on Germany and the world ‘slithered over the brink into the boiling cauldron of war’, as Lloyd-George put it.

A Liberal with Home Rule sympathies, 44-year-old Erskine Childers threw himself behind the Allied cause, primarily as an observer and intelligence officer for the Royal Navy, winning the DSO and the rank of Major.

Childers was appalled by the execution of the leaders of the Easter Rebellion in 1916 and subsequently joined Sinn Féin.

[His cousin Robert Barton is often said to have resigned his commission in the army in disgust at the executions but a lengthy statement he later gave suggests otherwise, and is something I hope to address before long].

Childers followed suit and, greatly admired by de Valera, became de facto Director of Propaganda for the underground Dáil cabinet in 1920.

He served as Chief Secretary for the delegation that negotiated the Anglo-Irish Treaty (which included his cousin Robert Barton) but steadfastly opposed the outcome.

The signing of the Treaty. Seated from left: Arthur Griffith, EJ Duggan, Michael Collins and Robert Barton. Standing from left: Robert Erskine Childers, George Gavan Duffy and John Chartres

During the Civil War, he became the principal spin-doctor and campaign advisor for de Valera and the Anti-Treaty forces.

In November 1922, the “damned Englishman” – as Griffith now referred to him – was arrested by Free State soldiers at his beloved home in Glendalough.

He was charged with possession of a gun, which had controversially been gifted to him by Michael Collins in happier times.

De Valera described it as ‘a tiny automatic, little better than a toy and in no sense a war weapon’.

But the Free State government had found the legal excuse to order the death penalty.

Diarmuid Coffey, who had sailed on the Kelpie in 1914, was apparently sent in to visit Childers with an offer to spare his life if he, presumably, transferred his allegiance to the Free State.

Childers refused the offer. Perhaps, not unlike Pearse six years earlier, he felt his death would give the anti-Treaty cause a new martyr to rally around.

Coffey had been best man at Robert Barton's wedding in happier times; like O'Higgins and O'Connor, their friendship was torn asunder by the unrelenting horrors of civil war.

On the day he died, Childers was 52 years old but looked 70 – his hair white, his face gaunt, his body racked by a constant cough that must have brought to mind the TB that carried away his parents.

At 6am on 24 November 1922, He wrote to Molly: “It all seems perfectly simple and inevitable, like lying down after a long day’s work”.

When the firing squad took their positions in Beggar’s Bush Barracks later that morning, he called out to them: “Take a step closer, boys, it will be easier that way”.

‘Of all the men I ever met I would say he was the noblest’, lamented de Valera. Robert Barton likewise mourned that his death was 'the wreck of all our hopes'.

Churchill was not so enamoured. “No man has done more harm or more genuine malice”, he exaggerated, “or endeavoured to bring a greater curse upon the common people of Ireland than this strange being, actuated by a deadly and malignant hatred for the land of his birth”.

The Childers legacy lived on through his son Erskine Hamilton Childers, who became 4th President of Ireland in 1973; his grandson Erskine Barton Childers, who served as Secretary General of the World Federation of United Nation Associations and his granddaughter Nessa Childers, now an independent MEP.

Turtle Bunbury's next book, 'The Glorious Madness - The Irish & World War One', will be published by Gill & Macmillan on 17 October 2014.

A new edition of FX Martin's 'The Howth Gun-Running and the Kilcoole Gun-Running', with a new introduction by Ruán O'Donnell & Mícheál Ó hAodha, is being published by Merrion Press to coincide with the centenary of the Howth Gunrunning.