Filtered By: Lifestyle

Lifestyle

Miyagi: Towns in recovery, 3 years after the Great East Japan Quake

Text and photos by SARAH GRUTAS

Photos show the devastation in Miyagi Prefecture after the quake and tsunami (clockwise from top left): Searching for bodies in a wrecked car in Minamisanriku; an 80-year-old in Ishinomaki is pulled from the rubble nine days after the disaster; a ship is brought ashore in Kesennuma; two men rest by uprooted trees near Ishinomaki's Okawa Elementary School, where only 34 of 108 students survived; and a soldier rescues a baby girl in Ishinomaki. Reuters

Last March 11, Japan marked the third anniversary of the disaster that took the lives of nearly 20,000 of its people. In Miyagi, the rubble and debris had long been removed and the ground leveled, save for a three-storey building near the port, toppled sideways, its metal frames jutting out and rusting under the sun—a lone remnant of the horrific event.

JENESYS 2.0

JENESYS 2.0 delegates learn how to put out fires.

Miyagi is one of the six prefectures in the Tohoku region that were heavily damaged in the disaster. The earthquake was a record-breaking magnitude-9.0 and the tsunami it created reached heights of up to 40 meters. During the program, we were able to witness how Japan rebuilt the community and the lives of its people.

Recovery and preparation

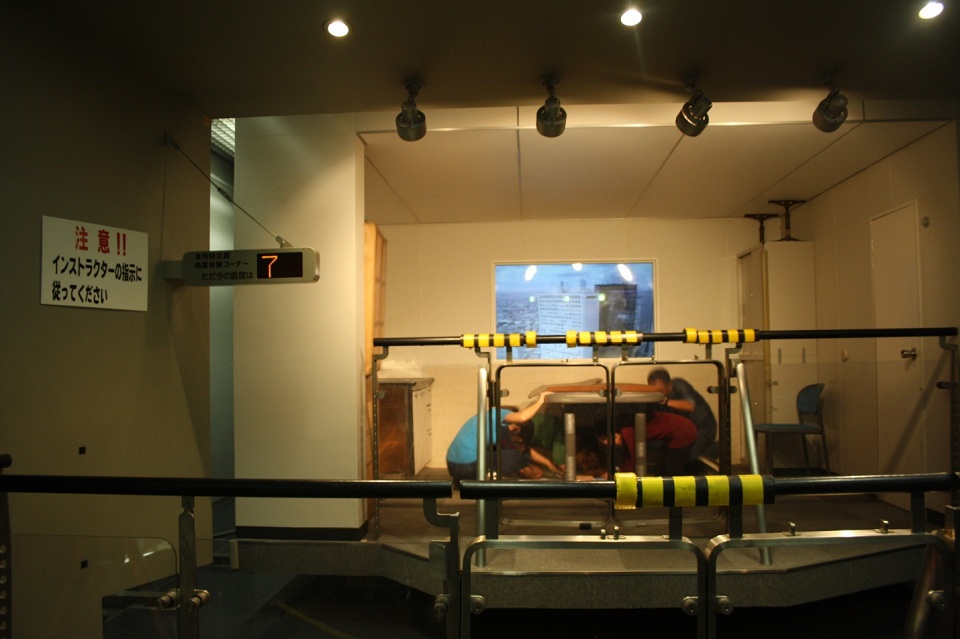

Intensity 7. Delegates in a simulator were taught what to do when an earthquake occurs.

In schools, drills are carried out twice a month—even students as young as pre-schoolers are not exempt. In Tokyo, the Honjo Bosaikan Life Safety Learning Center has constructed simulators of natural disasters like flood, typhoon, fire, and earthquake. Visitors, young and old, can come and experience what it feels like to be trapped in a car on a flooded street or during an intensity 7 earthquake.

We also discovered that the 2011 disaster and the subsequent reconstruction efforts were widely documented. The city government has produced documentaries and books about it. Our tour coordinator, Yutaka-san, related that it was important for them to document what happened and what has been done so that future generations can learn from it.

In a documentary the city government showed us, we learned that it took Sendai only 18 days after the disaster to restore water pipelines and reconstruct major thoroughfares, including the Sendai airport runway. These remarkable recovery mechanisms, along with plans for the future, will be discussed during the third UN World Conference on Disaster Risk Reduction, to be held next March in Sendai.

The coasts

Temporary housing projects up on a hill in Onagawa

We moved away from the capital and closer to the coastal villages, where the scars of the tragedy are still fresh. We passed by mountainsides newly shored with reinforced concrete grids. When our tourist bus pulled up at Onagawa harbor, bulldozers were busy pulverizing debris and leveling the ground. “It’s where the shopping stores and houses used to be,” said our tour guide. Hundreds of tetrapods were lined up at the port, waiting to be dispersed along the coastlines.

Families were relocated to a site where a stadium stood until it was destroyed in the earthquake. There the government built three-storey apartment buildings, where families can reside until they save enough capital to buy another property, away from the ocean. The government has declared the coast unsuitable for further residential development and therefore residents can never go back to their old property by the sea and rebuild their homes.

The government also decreed that a five-foot wall be constructed along the coasts, including the port—a ruling which some of the residents still oppose.

“The people, especially the older ones, grew up seeing the beautiful ocean. I think it’s the main reason why the residents oppose the construction of seawall. It will ruin the view. But they cannot do [anything] about it now. The government already decided,” our tour guide said.

The residents of nearby Kesennuma seemed to have the same sentiment about seawall construction. According to our tour coordinator, there had been a controversial and heated debate about it—with the local government wanting a 20-foot-high seawall.

What remains

WataMama also delivers bento meals to the elderly in the area.

And in the Watanoha district of neighboring town Ishinomaki, mother-volunteers put up a restaurant-cooperative called WataMama (a portmanteau of Watanoha and Mama or Mother) Diner. The restaurant is supported by Japanese non-government organizations. Since its opening last April, WataMama has provided employment to mothers in the community. It has also helped farmers in the area, as they source their ingredients locally.

The JENESYS program continues to bring in young people from the ASEAN and Oceania regions to learn about the reconsruction work in Japan after the 2011 catastrophe. Through this youth exchange, the delegates, who are also budding leaders and innovators, can gain other (or perhaps, better) perspective in reconstruction efforts, especially in emergency evacuation management and clearing operations, which they can eventually share to their community when they get back home. — BM/KG, GMA News

The next JENESYS trip will be from Sept. 20 to Oct. 8, 2014. It is open to Filipino college or masteral students, 18-30 years old, and with educational backgrounds in Disaster Management, Environmental Studies, or Asian Studies. To apply, visit the National Youth Commission website. The application period runs until August 1, 2014.

More Videos

Most Popular