On June 25th, a few hours before masked men forced their way into her Benghazi home and stabbed and shot her to death, Salwa Bugaighis issued a passionate plea to her followers on Facebook. "My people I beg of you," she wrote. "There are only three hours left."

Bugaighis meant three hours of voting time before polls closed in Libya's parliamentary elections. It was only the third nationwide balloting since the fall of Muammar Gaddafi in August 2011. A lawyer, human rights activist and mother of three boys, she had worked tirelessly since the early days of the Libyan revolution to lead her country toward democracy. The day of her death was like any other: she got up, she worked, and she pushed ahead.

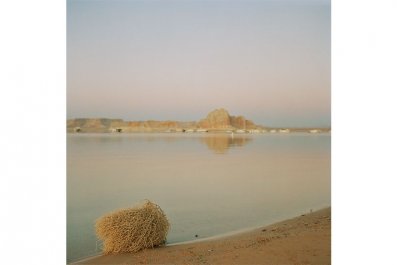

After returning from voting with her husband, Issam al-Ghariani, a member of Benghazi Council, Bugaighis stood on the roof of their elegant home, watching the street fighting nearby and describing what she saw on Facebook. Since the collapse of the Gaddafi regime in August 2011, Benghazi had seen little peace as warring militias battled each other relentlessly.

In September 2012, US ambassador J Christopher Stevens and three other Americans were killed when armed men stormed the consulate in Benghazi, but Bugaighis did not appear to be worried. This was a woman who had once stood up to one of Gaddafi's gangster sons, trying to talk him down after he came to Benghazi in the early days of the revolution. He asked Bugaighis and her sister, Iman, an orthodontist, to calm the protesters down. "We told him: no way!" she said to me in 2011. "We told him – we were demanding an end to corruption, a new constitution – things that you in the West take for granted."

On June 25th this year, she seemed worried that the people in Benghazi would be too frightened to come out and vote. She wrote on Facebook that the fighting was "intense ... Heavy smoke near the cement factory". Three hours later, as the polls closed, Bugaighis was dead.

Her husband was gone – apparently abducted by the five masked men who fought their way into her home and killed her, according to witness reports cited in the media. There has been no news of him since, nor has there been identification of her killers.

I met Salwa, Issam and Iman, in the spring and summer of 2011. The sisters, who were brought up in a wealthy, Western-educated family, were crucial players in the revolution. Their father had been a successful businessman, and they could have lived a life of plush exile in the US – but chose to live and work in Libya.

With Iman, in 2011, Bugaighis led the demonstrations at the Benghazi courthouse, which became the center of the city's unrest. There, activists, students and families of the missing who came to hang their photos, built a small city composed of tents and shanties, and they fought together to topple the 42-year rule of Gaddafi.

"Salwa was the first woman to initiate the -revolution against Gaddafi at a time when it took tremendous courage to come out in the streets ... She really was the mother of the revolution," says Peter Bouckaert, the emergencies director of Human Rights Watch. "She made a decision to live a life standing up for her fundamental beliefs without fear, and refused to be forced back into the kitchen by the Islamists and staunchly conservative tribal leaders of her country.

"Her death was not just another murder," says Bouckaert, who is "in despair" over the killing. "But a deep hatred of a woman who dared to be proud and charismatic in a society where extremists see no role for proud women."

I was startled when I first met Bugaighis in Benghazi. In her late 40s, she was tall, strikingly beautiful and – unusual for a Libyan woman – unveiled. She was not wearing the kind of clothes I saw other Libyan women wearing in those days, even modern ones – but a chic tailored jacket and trousers. She looked smart, Western, cool.

She led me into her home. She introduced me to her husband, and she began to talk about her work. Bugaighis was intent, she said, on forging a future for her country – a positive one, and one that would have a place for women.

This was the spring of the revolution, when Benghazi had been liberated. Gaddafi's forces were still fighting the rebels in other parts of the country, but in the eastern city, there was hope in the streets. People were talking in coffee shops. People were gathering at the port at sunset, talking about a future for the first time in decades. There was a sense of a new beginning. "We have so much to do," she said, fiddling with a pair of sunglasses on the table in front of her. "We need to get started as soon as possible."

She and Iman had started workshops attempting to empower women. She had launched a campaign to establish minimum quotas for female lawmakers in parliament, and she was anxious to get it moving. The mobile phone networks had just started working in Benghazi. Bugaighis picked up a phone and started punching out numbers, making appointments for me to see young women she was mentoring. She talked nonstop, pushing papers around, offering food.

But there were immense frustrations. Shortly after I saw her, she resigned from the National Transitional Council, accusing it of freezing out female members. She pointed out that the only female minister on the council at the time was an Islamic woman, who had been appointed to a lowly and subservient role.

In the three years following those heady days, the bright dream began to rapidly fade. Following Gaddafi's fall, in the absence of a steady government, militias were born out of the remnants of the anti-Gaddafi fighters and the Islamists. They became the main power, shouldering out moderates like Bugaighis, and many others who fought to bridge Libya's growing divide. It was demoralising to watch Libya, which had been so bloodily fought over, falling into the hands of radicalism. With political chaos, a lack of police and military force, the country fell into anarchy.

Then, her family became the victim of smear campaigns by conservative Islamists. Once she had joked to the journalist Lindsey Hilsum that of her three sons, "One was proud of her. One was scared. And the third? He's just annoyed that his school trip to Greece has been cancelled!"

But now it was painful. Iman decided to take a quieter route to protect her children, but Bugaighis kept pushing. "One month ago, they tried to assassinate my son," Bugaighis told National Public Radio a few weeks before her death. "And he was driving my car, so maybe they want me. Maybe they want my family ... or ... but this is not about Salwa – you know, there are many, many activists ... [they have] targeted."

During particularly difficult periods, the family left the country, but they always returned. On June 25th, they went out to vote and later Bugaighis spoke to al Nabaa, a local TV station. "There are people who want to foil elections," she said, with gunfire in the background. "Benghazi has always been defiant, and always will be despite the pain and fear. It will succeed."

A few hours later, she was dead.