WASHINGTON -- A new report suggests American law-enforcement doesn't just stop terrorism suspects -- it creates them, too.

The study by Human Rights Watch bemoans an over-aggressive approach where the FBI will identify someone who fits a possible terrorist profile; urge that person to participate in an attack; provide the necessary materials; then, finally, make an arrest.

The study examines sweeping changes to police tactics since the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, an era of increased pressure on law-enforcement to intervene before crimes ever get committed.

This climate of urgency has led police to overstep moral guidelines, according to the 212-page study entitled Illusion of Justice: Human Rights Abuses in U.S. Terrorism Prosecutions.

"The FBI may have created terrorists out of law-abiding individuals," said the report, released Monday.

"In many of the sting operations we examined, informants and undercover agents carefully laid out an ideological basis for a proposed terrorist attack, and then provided investigative targets with a range of options and the weapons necessary to carry out the attack.

"Instead of beginning a sting at the point where the target had expressed an interest in engaging in illegal conduct, many terrorism sting operations that we investigated facilitated or invented the target's willingness to act before presenting the tangible opportunity to do so."

The report said it wanted to examine police tactics that had led to 500 terrorism convictions in U.S. courts since 9-11. Citing previous studies, it said half these cases involved informants and that the informant played an active role in the plot 30 per cent of the time.

The authors interviewed 215 people connected to 27 American terrorism cases.

The report said some of the people targeted suffer from mental illness or financial problems. It said they were given the motive and the means to commit crimes they might never have ever considered.

In two cases, it said suspects were even given money to participate in a plot.

The study quoted a New York judge in a case involving a plot to shoot down military planes and bomb synagogues. That judge said, of one suspect, that only the government could have succeeded in making a terrorist out of him -- because his "buffoonery is positively Shakespearean in scope."

Said another judge at a different stage in the same case involving the so-called Newburgh Four: "The government came up with the crime, provided the means, and removed all relevant obstacles."

The accusation of police entrapment has also been leveled in a U.S. case related to Canada's Via Rail attack suspects.

Ahmed Abassi was accused of plotting to organize a U.S-based terrorism cell, and prosecutors alleged he worked to radicalize one of the two people accused of planning to blow up a passenger train in Canada.

But a court filing for the Tunisian national said that he never even wanted to go to the U.S., and actually just wanted permission to re-enter Canada and be reunited with his wife there.

The document said a police informant:

- Lured him to the U.S, with a promise to help get him into Canada.

- Helped him get a U.S. visa.

- Reached out to his mother, father and wife and got them to encourage him to go to the U.S.

- Arranged a meeting with one of the Via Rail suspects.

The court filing said Abassi repeatedly rejected entreaties for him to get involved in a terror plot -- although his stated reasoning, apparently, was that the plans presented to him weren't devastating enough.

Last week, after the case against him crumbled, Abassi was sentenced in New York to the 15 months in prison he had already served.

The Human Rights watch report has now urged a series of procedural changes, including a more go-slow approach to launching a sting operation.

It also criticizes U.S. entrapment laws.

It says the U.S.'s wishy-washy definition of entrapment fails to meet international legal standards. In the U.S., defendants must show not only that the government induced them to commit an act, but also that they were not "predisposed" to committing it -- with that latter part being especially difficult to prove.

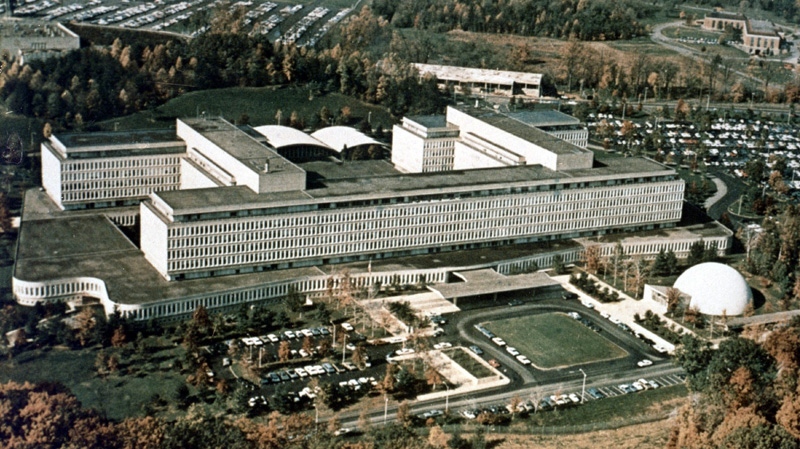

On the FBI website, an agency instructor says terrorism poses a unique legal challenge.

"Law enforcement agencies face a difficult task," said David Gottfried, an instructor at the FBI Academy and bureau's assistant general counsel.

"In the aftermath of 9-11, it no longer proves sufficient to solve crimes after people have committed them. Rather, a top priority of law enforcement is preventing another terrorist attack against U.S. interests. The American people expect federal, state, and local law enforcement officers to proactively prevent another terrorist attack, and even one failure is unacceptable."