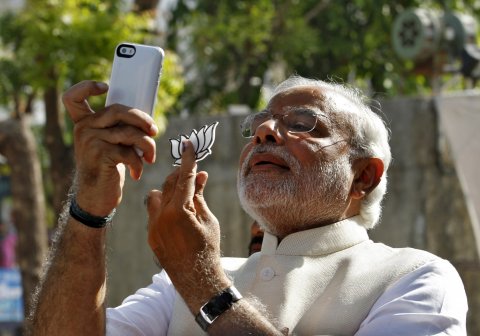

When US Senator, and former presidential candidate, John McCain met with India's newly elected prime minister Narendra Modi earlier this month, he joked, "You have the greatest expectations since the Second Coming." The comment hardly overstates the euphoria in India today: Indians do not hope for an economic miracle from Modi – they assume it will happen and they are impatiently checking their watches wondering when, to borrow Modi's campaign slogan, the achche din (good days) will be coming.

It may take a while, or so said Arun Jaitley, India's minister of finance, minister of defence and Modi's long-time ally, as he presented the country's annual budget last week. Jaitley alluded to the prime minister's landslide victory in May. "The people of India have decisively voted for a change. The verdict represents the exasperation of the people with the status-quo. India unhesitatingly desires to grow," he said. But he also tried to quell expectations. "This is the beginning of our journey, not the end."

Investors and economists, both foreign and domestic, watched and live-tweeted the rollout of the budget, waiting for the sound of India's gilt doors swinging open. Instead all they could hear was the door cracking slightly ajar.

The stakes for those watching are high. After India's record growth for the first decade of the 21st century, with GDP touching 9% in 2010-11, the economy has stalled in the past four years, and with strict regulations hampering foreign direct investment and notorious amounts of red tape to untie, the idea of investing in India has been perceived by many as a risk-riddled enterprise.

There was one state, however, that offered a slightly easier path to foreign investors: Gujurat, India's western state of 60 million people, known for its entrepreneurial diaspora and its business-friendly chief minister who delivered a higher rate of growth than the national average in his 10 years in charge from 2004-2014, Narendra Modi.

The promises Modi put on the table during the campaign are alluring: 100? new smart cities, a bullet train between the major ones, a cleaned up Ganges River, tax reform, and an end to black money. During the campaign, the politician from Gujarat chided the incumbent Indian National Congress, who in 60 years in power had failed to bring economic prosperity to India. "You give me 60 months and I promise you a life of happiness and peace," Modi said at a rally this January.

Until the budget was released last week, it was anyone's guess how Modi would prioritise his promises. Jaitley's 44-page budget offered the most concrete clues about this government's direction. The verdict ran the gamut from optimism to feelings of déjà vu, but most could agree on one thing: India is slowly – and finally – opening itself up to the rest of the world. Jaitley announced he would be raising the limit on FDI in two key sectors, defence and insurance, from 26% to 49%. Separately, plans to allow foreign investment into India's enormous railway infrastructure were announced. While he estimated that GDP would hover at around 5.5 % for the upcoming year, Jaitley said he aimed for an increase to about 7-8 % in the next three to four years.

There was one, loud, false note. Jaitley did not mention plans to remove the now-controversial retrospective tax laws, which were established during the previous government's rule and permitted it to claim taxes on past deals. One of the most high-profile targets was the UK telecom giant Vodafone, who in 2007 acquired an Indian telecom -company, Hutchison Whampoa, to create Vodafone India. Under the new law, Vodafone would be required to pay back taxes on that deal and today, Vodafone and India are still in international arbitration over the $2.5 billion the Indian government believes it is owed.

Some, including those who spoke favourably of Modi during the campaign, expected more. "This budget essentially blew an opportunity to reset the so-called 'India story' in the eyes of the world. Instead of declaring that India is again open for business after a disappointing past few years under the previous Congress-led government, the first Modi budget suggests tentativeness and confusion," said Sadanand Dhume, an Indian scholar at the American Enterprise Institute.

On the other hand, creating a climate for investment is about more than enacting laws, Modi's way of governance has proved that it is serious about getting rid of the bugbears that have haunted India's reputation in the business world in recent years: corruption and red tape. When Modi was sworn in as India's 15th prime minister on May 26, he floated a new motto: maximum governance, minimal government.

On his first day in office, he created an investigative team of former judges and regulators to start hunting down the estimated $2 trillion of black money that is stashed as concealed assets overseas. Last month, Jaitley, announced that Switzerland would share with Delhi a list of Indians holding black money – a statement that the Swiss did not confirm.

Politically, his fellow world leaders have been scrambling to make nice with Modi, despite the fact that many have shunned him in the past. The US had denied Modi a visa in the aftermath of the bloody Hindu-Muslim riots that occurred in Gujarat under his watch in 2002. Now, Barack Obama has issued a formal invitation to him to visit Washington in September.

Modi has assured a nation frustrated by government ineptitude that India will gain so much respect under him that the country will no longer be spoken of being in second or third place in Asia – the world will soon be India's.

"I want to make the 21st century India's century. It will take 10 years, which is not very long," he said after his victory, alluding to a desire for two terms as prime minister.

MR DEVELOPMENT

For a politician who for many years has not been able to shake off the adjectives "polarising", "divisive", "authoritarian" or "communal", Modi is today basking in a rare, almost universal hagiographical glow. "It is as if India is beginning again," a prominent Indian columnist, Santosh Desai, wrote in the Times of India. The Guardian said that Modi's victory "may well go down in history as the day when Britain finally left India".

That people – voters and investors alike – have faith in Modi's ability to turn the economy around, may be because his own rags-to-riches story reveals a ruthlessness of ambition. While many predicted that Modi's Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) would triumph over an increasingly lacklustre coalition government led by the Congress party, few foresaw the crushing defeat that the 63-year-old Modi would hand to the incumbents, who have ruled India for 49 years. The BJP won an absolute majority of 282 seats in the lower house of parliament – the best any party has done since 1984.

Two months on, the corporate signs congratulating Modi have mostly been removed in Ahmedabad, Gujarat's most populous city and its de-facto capital. Teenagers still wear Modi shirts and swap stories about where they were on May 16 when Modi's victory was announced. Gujarati tourists are routinely stopped in their travels across the country and interviewed like celebrities: "Tell us what our future looks like," they are asked, "Tell us all the things that Modi has done in Gujarat that he will do for the rest of India."

Modi, whose popularity right now exceeds even that of Gujarat's other proud son, Mahatma Gandhi, is India's first prime minister to be born after Independence in 1947, as well as the first from the economically and socially marginalised group known as the other backward castes. His supporters see him as an economic visionary, a strong politician who is unafraid to muscle India towards prosperity and out of the shadow of its over achieving Asian sibling, China. But a significant number, including some of Modi's supporters, are warning that a new India is coming but it may not be the one people expect.

Achyut Yagnik, the co-author of Ahmedabad: From Royal City to Mega-city, says that the key to Modi is in understanding Gujarat's mercantile culture. "As long as Gujaratis are making money, they couldn't care about the government or what the government does," the 71-year-old Yagnik says. Throughout his campaign, Modi seemed to embody the belief that government functions best when it steps aside and lets the market help society reach its potential.

Among the companies Modi persuaded to invest in his state were Ford Motors (who announced a $1 billion factory in 2011) and PSA Peugeot Citroen. India is now the world's second largest car market (after China). Given Modi's Gujarat roots and his positive experience with foreign investors there, Yagnik expects Modi to open up India's economy. "He is also trying to take credit for everything good in Gujarat and he has silenced anyone who will challenge him on this," Yagnik said.

Business leaders in Ahmedabad see it another way. Ramesh Mehta, a man in his late forties, who runs an industrial cleaning company, said that Modi has streamlined government functions in Gujarat by placing many of them online and by shortening the approval process for contracts. He even implemented a rule, he told me, that a piece of paper in the Gujarat government is never allowed to be touched by more than five people. Since moving to New Delhi, Modi has masterminded a clean up of the notoriously convoluted and inefficient bureaucracy, starting by organising a mass de-clutter and sanitisation of government offices.

However Modi's love of large construction projects, which reshape a city's landscape, create jobs, and promote tourism have a darker side. Bachchan, who is in his early 40s, believes only the elite will benefit from Modi's rule. He grew up along the Sabarmati River, which cuts through Ahmedabad and along whose banks Gandhi started his ashram and launched his non--violence movement.

In 1997, the city government of Ahmedabad began building a 10-km promenade on both sides of the river. The project was accelerated and completed during Modi's tenure and he has often cited it as an example of Gujarat's successful development model. As a result of the riverfront construction, Bachchan and 3,500 other families were forcefully resettled into units far outside the city.

"Modi took us away from our land and from our livelihood and put us into this prison," Bachchan says. Hari Prasad is his real name but since he grew his hair in the style of the Indian actor Amitabh Bachchan, the nickname stuck. Bachchan, who is Hindu, lives on one side of the housing colony known as "Hindustan". On the other side is a row of Muslim homes known as "Pakistan". Violence often breaks out, he says, unemployment is high, and few children graduate from high school. He would like to leave the area but has little choice.

In today's Ahmedabad, Bachchan finds himself priced out. His home is so far outside the city centre that he cannot afford the daily transportation into the city. And yet while Bachchan blames Modi for his displacement, he also voted for the BJP. This is a testament to Modi's overweening victory – even those who have not benefited from Modi's policies (or have been adversely affected by them) still fell in line. "I believe in Modi," Bachchan says. "I am a Hindu, after all."

Most residents of Ahmedabad have not seen or heard about residents like Bachchan. The city's problems are at its fringes, hidden away from the -middle-class gaze. India's booming middle class, would rather not be reminded about the country's 70 million who lack electricity or the 363 million who, as of 2012, live below the poverty line.

Meghna Desai, a 26-year-old lawyer in Ahmedabad, meets her friends every morning at the Sabarmati riverfront promenade to jog. The promenade has a wide walking path, ample trash cans, and bright lanterns. Desai, who also voted for the BJP, says that walking with her girlfriends without any male accompaniment early in the morning was something few women could enjoy elsewhere in India. "This is to his credit," Desai says. She does not need to explain who she means.

Desai says that Modi is looking after her interests and that she has little reason to be critical of him. "We all benefit from this riverfront," she says. Technically, she is right – it is open to the public but poor or low caste residents are unlikely to use the space. Bachchan says he feels unwelcome and sad when he sees the place that once was his home. When I ask Desai if she knew about the tens of thousands displaced from the riverfront, like Bachchan, she shakes her head.

"No, I do not know about them but I think they are in a better place over there. Who wants to live by a river," she says.

LIFE ON THE EDGE

However efficient Modi's administration becomes, one allegation will cast a shadow for a long time to come: that the man whose career and character was formed within the ranks of one of the nation's most hardline Hindu nationalist organisations, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), will never convince the nation's 180 million Muslims that they are safe on his watch. And the threat of violence is bad for business too.

Five months after Modi became Gujarat's chief minister, on February 7th, 2002, a train compartment of Hindus was attacked by Muslims, in the Gujarat city of Godhra. Retaliatory violence broke out immediately, leaving more than 1,000 dead, almost all of whom were Muslims. Human Rights Watch accused Modi of complicity in the violence and failing to protect innocent lives.

More than a decade later, a Supreme-Court-appointed special investigative team found no wrong-doing on Modi's part. Manoj Mitta, a senior human rights journalist in India, writes in The Fiction of Fact-Finding: Modi and Godhra, that the Indian legal system has a poor record of indicting the country's economic or political elite. Mitta calls Modi's approach to justice "cavalier" because of the unwillingness of the courts to ask him tough questions about his role in the 2002 riots – and for Modi's refusal to answer these questions.

Twelve years on, many who suffered in the Gujarat riots still struggle to piece together their lives. On February 28th 2002, Abida, who asked me to change her name, lost her husband when a Hindu mob chopped off his limbs and burnt him alive. Abida escaped by leaving in a car full of corpses. Today Abida, 45, lives in Juhapura, the all-Muslim ghetto, in a home provided to her at a subsidised cost of around $1,000 by an Islamic charity. She had to pay some of this amount out of her own pocket – the Gujarat state only gave her $845 for her burned-down home.

Hindu-Muslim violence has remained common in Ahmedabad. According to Ghanshyam Shah, a retired political science professor who lives in Ahmedabad, many riots are stirred up by partisan politicians to solidify their voter bases. Shah, who is Hindu, believes Modi was complicit in the violence: "He could have stopped the violence. But he knew he would benefit from the riots and he did," says Shah. When Modi became chief minister, he was unknown and unpopular, Shah says. After the riots, he managed to gain the sympathy of Hindus "by creating the Muslim enemy". After Modi secured his Hindu vote bank, "Then only did Modi start reaching out to Muslims."

One of the legacies of Modi's rule, Shah believes, is ghettoisation, something he fears will become more widespread across India. "People have been pushed into a corner and neglected. And because the state fails, the grip of Islamic groups becomes stronger." Abida concurs. Each year, conservative Islamic groups in Juhapura, many funded by wealthy Muslims in the UK, distribute dates, honey, and milk to the needy like Abida during Ramadan, the Muslim month of fasting and prayer. The handouts, she says, are not enough. "My daughter's education costs 400 rupees ($6.75) per month," Abida says. "I do not have this money."

There is a new mosque near her home – built with foreign funds – complete with fans, carpet, and running water, but only men are allowed inside. But there is no drainage at her home and when the monsoon arrives in a few weeks, Abida knows her house will flood, the water will seep in the space between her skin and her nails, and aggravate her bacterial infection. She has tried to move out but she has few options: her in-laws have refused to let her remarry, she has little education, and as a seamstress, she counts the days when she makes 150 rupees ($2.53) as Allah ka karam – God's generosity.

Since the 2002 riots, Modi's government has blocked Indian national government scholarship funds that would have benefited children like hers. The Gujarat government has also refused to rebuild the hundreds of mosques and Islamic shrines that were destroyed in the riots, despite the BJP's election -manifesto pledging to protect heritage in India. According to local Islamic groups, Abida says, the solution is to marry Abida's daughter off in a few years, ideally to a man from Chicago or Bradford. "It will never be the same," she says, referring to her life since the riots.

Jaitley's budget has allocated around $17 million to modernise Islamic schools, known as madrassas, a fact that frustrates Abida. "We Muslims are criticised when we send our children to madrassas and we are blamed for not being as educated as the others (ie Hindus). Modernising madrassas is useless. I want a normal school for my daughter," Abida said.

Kazi, who lives in the same Muslim ghetto of Juhapura, shares her views. He was speechless as he watched the returns on May 16th. In the Lok Sabha the lower house of parliament, there are now only 22 Muslim members out of 543, the lowest Muslim representation since 1953.

Kazi worries that Muslims are becoming politically irrelevant in India. "Modi won by consolidating the Hindu vote and the results showed that the Muslim vote against Modi was inconsequential. It is dangerous because now any party can side-step and ignore Muslims."

Each week, Kazi and his friends meet for a discussion over cups of chai. "As Muslims, we need to ask ourselves tough questions, especially about why we support the Congress party," he says. "The BJP openly targets us but the Congress party just uses us," he says.

There have been more Hindu Muslim riots under the Congress party's watch in Gujarat than the BJP's – a fact, Kazi says, that should force Muslims to be more introspective.

During his election, Modi softened his stance on Muslims, holding regular meetings with Muslim leaders and promising to help the community. Kazi is not convinced. "I want to believe Modi can change," Kazi says, looking at the unpaved road outside his home, where his two children are playing cricket. "But I do not see any proof."

SILENCE THE CRITICS

The international community, and most in India, seems to have largely forgotten the riots. "He's now the elected leader of the world's largest democracy. I don't particularly like the stories I read about his involvement, but the people in India elected him as their leader, and we need to deal with it," said John McCain.

They may be able to forgive him for the riots, but they will be less easily soothed if Modi fails to rejuvenate India's economy.

Rafat Quadri, a Muslim Gujarati journalist, believes the Indian press will be the first group to buckle in this climate. She should know – at one point, she was so close to Modi that he came to her wedding. Today things are different.

"I have reported on so many leaders in Gujarat but I have never seen someone as unwilling to speak to the press as Modi," she says. "He distrusts us. He does not want us to write bad things about him. That is clear." A few days after becoming prime minister, Modi told government ministers and bureaucrats that they were forbidden to speak to the press.

Quadri's prediction has already come true: last week, an Indian website took down an article by journalist Rana Ayyub that was critical of the BJP's new president, the controversial Amit Shah, who was forced to leave Gujarat because he faced charges of ordering extrajudicial killings. "Never has my pen been silenced like this before," Ayyub said.

It should be noted that censorship in India, whether by the state or by private entities, is not unique to the BJP. Salman Rushdie's controversial book The Satanic Verses was banned in India before it was in Iran – a decision made by the Congress party, widely interpreted as an attempt to pander to its Muslim vote bank. Most of Modi's voters favoured him because they were in equal parts attracted by his economic vision and frustrated by the Congress party, but a small, vocal minority sees Modi as the man who will transform India into a "Hindu nation".

In the Khadia neighbourhood of Ahmedabad, a Hindu nationalist stronghold, I meet an 18-year-old first-time voter named Chirag Chauhan, who is still proudly wearing a bright orange Modi shirt. "Now Pakistan and Bangladesh will be silenced," Chauhan says.

I try to shift the conversation to development and ask him how Modi will promote economic growth. "Modi will first silence the critics," he says.

Just who are these critics, I wonder. "The Muslims and the journalists."

Gujarat remains tense: the night before Modi's swearing in, a clash at a wedding in Ahmedabad led to fresh Hindu Muslim violence, injuring four people. In Pune outside of Mumbai, a 24-year-old Muslim boy was beaten to death by a group of Hindus after they took offence at a Facebook picture of a Hindu leader that they believed, incorrectly, he posted.

Modi would of course prefer that his supporters, as he has done, shift focus to development. But this too comes at a risk. Nilanjan Mukhopadhyay, the author of a biography Narendra Modi: The Man, The Times, fears many will be let down when the numbers do not meet expectations. "Forget about 60 months, young people will not even give Modi six months. They are impatient. They want results," Mukhopadhyay says.

Faizan Mansuri echoes this sentiment. The 20 year Ahmedabad resident is an unlikely candidate to be a Modi supporter: he is a Muslim, his parents lost friends in the 2002 riots, he lives in the Muslim ghetto near to Kazi, and he was denied a flat near his university because of his Muslim name. But the first-time voter supported Modi.

"I graduate in two years and I believe Modi can change the economy, which would be great because I will be on the job market soon," Mansuri says, with a wide smile.

Like a lot of young people in India, Mansuri's style – fake Nike shoes, imitation Beats headphones – is largely influenced by America's urban culture but his fascination with the US ends there. Mansuri, like a growing legion of young voters in India, looks towards China, and not the United States, as a model to emulate. China succeeds, Mansuri reminds me, because it has a strong leader who is not questioned.

Before he returns to his college, Mansuri inserts his USB internet stick into his laptop and opens up his Facebook page to add me as a friend. We both wait as the page loads.

"Did you know that India has one of the slowest internet connections in the world?" he says. "China is much faster. Korea is like 10 times faster. So India needs to change. And I hope it changes soon."