On the morning of Wednesday, April 15, 1964, a 22-year-old schoolteacher named Gail Wise walked into a Ford dealership on Cicero Avenue in Chicago,

unaware that she was about to make history. She wanted a convertible. The dealership was out, except for one. A salesman led her into a back room, where she saw a car under a tarp.

"And there it was," she remembers, sitting in her home in Park Ridge, Illinois. "I had never heard of the Mustang. It hadn't been launched yet." She bought the car and drove it out of the dealership that night.

"I was very popular," she says today. "I felt like a movie star!"

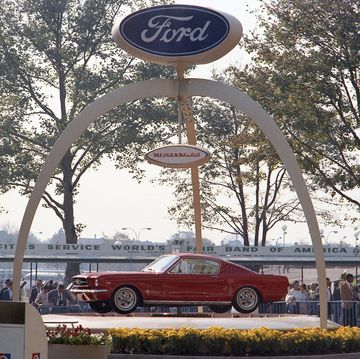

Wise was the first Mustang buyer. She paid $3447.50 for a Skylight Blue convertible, which she still owns. Two days later, on April 17, 1964, Lee Iacocca and Henry Ford II unveiled the car at the New York World's Fair.

"Walt Disney cut the ribbon for us," Iacocca noted afterward. "We couldn't have asked for a better launch."

Across the nation, a sales frenzy erupted. About 22,000 orders came in the first day. In Garland, Texas, the car sold out so fast, the last one had to be auctioned off, and the winning buyer slept overnight in his Mustang until his check cleared the next day. In Seattle, a truck driver was so enthralled by the sight of a Mustang in public that he drove his truck through a showroom window.

Two weeks after the launch, Ford Motor Company posted an all-time monthly sales record. Sales could've been higher, Iacocca told the Wall Street Journal, if the company could only build the cars faster. The automaker was able to deliver only about 1200 Mustangs a day.

By the end of the year, Ford could claim $1 billion in Mustang sales, $224 million contracted out in parts business for the car, and 18,000 jobs added. Even the new Mustang sunglasses were flying off the rack.

"Our hotcakes sell like Mustangs!" read a sign in a Manhattan diner window.

This April marked the 50th anniversary of the car's launch, which, in terms of societal influence, still stands as the greatest of them all. No American car has ever made its way into popular culture with such speed and depth. So, how did it happen? And who was responsible?

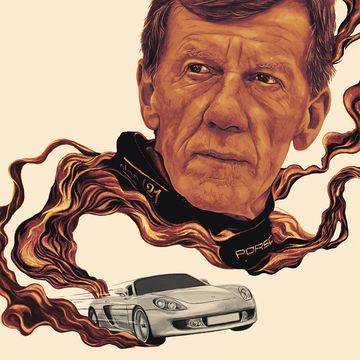

Some misconceptions of the car's origin have crystallized in the public consciousness. And yet many of the seemingly apocryphal facts out there are spot on. While all cars represent the collective ambitions and political struggles of the people who dream them up, the birth of the Mustang is the story of two particular icons: one, a striver, the son of immigrant Italians, and a child of the Great Depression; the other, one of the most powerful chief executives and corporate figures, a man who was, at the time, suffering something akin to a midlife crisis and on the verge of a nervous breakdown. They were two men who shared a ruthless desire to win in the most cutthroat business on earth. When they met in the middle, a car with a galloping horse on its badge was born—a car still galloping today.

On November 10, 1960, Lee Iacocca was in his office in the Ford Administration Building. Since he was young, growing up in Allentown, Pennsylvania, he'd dreamed of working for Ford of Dearborn, and he'd climbed his way from lowly engineering trainee to Ford's head of truck marketing. Still, he had something burning in him, a voice in his ear saying there was more out there. When his phone rang that day, it turned out there was.

"Mr. Ford called me over at 10:20 am," Iacocca said. "You never forget these things."

WATCH: a video about the original Mustang concept car

Iacocca motored over to a Dearborn building known as the Glass House, Ford's world headquarters. He took the elevator to the 12th floor. When the doors opened, he walked into what people have jokingly called "executive heaven," a sprawling, carpeted room dominated by three wall-hung portraits: Henry Ford, Edsel Ford, and Henry Ford II, the three generations of men who had run this famed empire. Iacocca had met Henry II before, but they'd never shared a conversation. Now he was shown into the man's corner office.

"It was like being summoned to see God," Iacocca recalled.

"We like what you are doing," Henry II told Iacocca that morning, "but we have something else for you. How would you like to be a vice president and general manager of the Ford Division?"

Iacocca walked out of that office as boss of the flagship brand of the world's second-largest corporation.

Even before that day, he had dreamed of a certain automobile. "I had a vision in my mind before I became the Ford Division general manager," Iacocca said, looking back, "of a four-seat sporty car that would be new to Ford and the American auto industry."

VIEW: The evolution of the 1966 Ford Mustang Mach 1 concept

One misconception of the Iacocca legend is that he "discovered" the youth market. Not true. 76 million Americans were born between 1946 and 1964. By the early 1960s, much of American industry was already thirsting for the attention of what Iacocca later called "the buyingest age group in history." Smart marketers could smell the money, not just at car manufacturers but at breakfast-cereal companies, insurance agencies, and anywhere anyone had something to sell. In the early days of Iacocca's tenure as Ford Division chief, he saw the cash potential spiral upward. Ford's competition had already tapped into the new thirst for style and adventure that was sweeping the nation. It was led by young car buyers.

At the time, Ford Motor Company was dominated by the vision of Robert McNamara, whose promotion to company president (the first man not named Ford to hold the position) cleared the way for Iacocca to gain power. McNamara was a brilliant, Harvard-trained executive who would later serve as Secretary of Defence under John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson. In 1960, he launched the Ford Falcon, a compact Volkswagen fighter with a relatively pedestrian technical blueprint. Regardless of its humble bones, the Falcon struck a nerve: In its first year, it hit a record for a new-car launch, with 417,000 examples sold.

McNamara's idea of America was rooted in the recessionary late 1950s. As one journalist said of him: "He wears granny glasses and he puts out a granny car." Meanwhile, General Motors had already begun to target youth. In the early 1960s, GM was selling high-performance cars with Hollywood styling, like the 1962 Pontiac Grand Prix and Chevrolet's compact, rear-engined Corvair Monza.

"You can't sell basic transportation," said legendary GM and Chevrolet executive Semon "Bunkie" Knudsen in 1962, two years before the Mustang launch. "But when you add wire wheels and hotter engines and fancy trim, you can't keep the cars in stock."

VIEW: The evolution of the Ford Mustang II

McNamara's "Plain Macs," as cars like his Falcon were dubbed, couldn't compete. GM's market share shot up from under 50 percent at the turn of 1960 to more than 60 percent in May 1962. Two years into Iacocca's tenure at the top of the Ford brand, Businessweek published this tidbit: "In today's auto sales race, the Ford Motor Company must feel like the man in a bad dream who races like mad only to find himself farther behind than ever."

Iacocca was 36—eight years younger than McNamara. And unlike bean-counting McNamara, Iacocca was a car guy. He could see a new America emerging. In his first 18 months on the job, he upgraded Ford's lineup with a new coat of marketing paint, turning the staid Galaxie sedan into the Galaxie 500/XL, and not long after that, McNamara's Falcon compact into the "sporty" Falcon Sprint. But he needed something bigger—an all-new model that would plant his flag in the heart of the Motor City.

He created a think tank he called the Fairlane Committee. The job: to noodle into the heads of these new car buyers and win them in spades. "As early as 1961, it was becoming apparent that the character of our market was experiencing a major upheaval," Iacocca said in 1965. "The first job was to identify what kind of product the new market was restlessly groping for and couldn't find. From exhaustive market research, the picture of a new car—unlike anything then available—began to take shape."

VIEW: The Fox Body Mustangs that almost were

Now consider the viewpoint of Henry Ford II, a man defined by his name since the day he was born in Henry Ford Hospital, a man who rode around in a massive, monogrammed Lincoln limousine. He had earned his place in the Detroit pantheon; after World War II, while still in his twenties, Henry II had led a fossilized company back from the brink of bankruptcy and, in one of the greatest business comebacks in history, turned it into a modern international corporation. He carried the weight of his family empire on the shoulders of his 250-pound frame. There was no "separating the man from the company—Mr. Ford from Ford," according to one of his closest confidants, Walter Evans. "The company always came first, ahead even of family."

In the early 1960s, however, Henry II's company began to suffer a significant identity crisis, in both its executive offices and its salesrooms. Henry II had never gotten over the Edsel debacle. In 1958, he launched an automobile named after his beloved and deceased father Edsel, who served as Ford Motor Company president from 1919 to his untimely death in 1943. The Edsel was the most expensive car launch in the company's history, and it crashed and burned after two years. The car's expansive size didn't connect with buyers during a recession, and its styling featured a grille that resembled a certain female body part. The Edsel was the biggest car flop of its time, a permanent stain on Henry II's soul, and it had cost his company hundreds of millions of dollars.

In 1963, Henry II's company lacked an anthem. As Frank Thomas of the J. Walter Thompson advertising agency, which handled Ford's account, put it: "Now I imagine you can say [with] Chrysler that engineering is its theme; and GM, its styling and general excellence. But what was Ford's? It was a crucial question facing the company."

GM's fortunes were skyrocketing. At the same time, Detroit's Big Three had to consider foreign competition seriously for the first time. Americans bought nearly 230,000 Volkswagens in 1962, and eventual monolith Toyota had debuted its first car stateside.

Ford was in desperate need of something—but what?

VIEW: The Front-Wheel drive Ford that almost became a Mustang

Iacocca thought he had the answer. At the company's Thursday-night Fairlane Committee planning dinners, his team first had to consider how it would build a new model on a shoestring budget. There was no way Henry II was going to go for another $300 million launch after what happened with the Edsel. Iacocca credits his special assistant Hal Sperlich with the idea of building a new model using components already on hand. They could use the Falcon chassis and engines and build a new body and greenhouse on top.

"Sperlich came up with the idea of using the existing Falcon chassis as the basis for the car, and that allowed us to go forward with low development costs," Iacocca said. He credits product planning chief Don Frey, an engineer with a PhD, as another key brain on the project. As Frey said then, Iacocca was "the coach of the Mustang project. I was the quarterback."

The next order of business: How to make the model appeal to a huge audience, at a price that Americans could afford? It had to grab hot rodders as well as female Chicago schoolteachers. It had to be class-independent, to appeal to buyers at any income level. The Fairlane Committee came up with the idea to price a discreetly outfitted stock model inexpensively, with a huge menu of add-ons (engines, wheels, tires, transmissions), so the car could be customized for the buyer in the showroom. In this way, the price could be made to match a customer's wallet. As Iacocca put it in 1964: "It's a car with three faces"—economy, sports, and luxury.

Then, they had to figure out what the car would look like. Iacocca learned valuable lessons about the auto game from McNamara. For example: "He taught me never to make a major decision without having a choice of at least vanilla or chocolate. And if more than a hundred million dollars were at stake, it was a good idea to have strawberry, too."

VIEW: Sketches of what the fifth generation Mustang could have looked like

The design team, under ace artist Eugene Bordinat, produced no fewer than 18 clay models for this new car. Veteran designers were teamed with young guns in a bake-off to find a winner. Today, the design that came out on top is most often attributed to designer Gale Halderman, though in his autobiography, Iacocca credits an assistant stylist named Dave Ash.

Up to this point, at the turn of 1962, thousands of hours had gone into the new product, but the car still had a vague shape and no name. And Iacocca, though renowned for his sales prowess, had yet to sell the idea to his mercurial and demanding boss.

One day, Iacocca dragged Henry II out of his office to see a clay model of the new car. Iacocca had Chevrolet's lineup in a parking lot and Ford's across from it. In the Ford lineup stood this clay, showing where it fit in and how it could stand up to Chevy. Henry II, still reeling from the Edsel affair, was terrified.

"Enough of that sh**, Lee," he said. "We got our asses lost on the last one. Who needs another?"

The man known as the Deuce then stormed off—straight to the hospital. He was bedridden for a month, officially with mononucleosis, though the word on the street was that he was suffering from a debilitating case of nerves.

At the time and still today, Iacocca has spoken of the volumes of research that went into the Mustang launch. In fact, he did invest wildly in fact-finding analysis. Yet some have argued that his efforts were aimed at selling the car to one man: Henry II. And that the real fuel behind the Mustang idea wasn't market research at all but what Iacocca called "a hunch."

VIEW: The 50th Anniversary 2015 Ford Mustang Spy Shots

In Ford's Design Center in the spring of 1962, Iacocca made a more formal presentation, backed with tons of bean-counter numbers, to Henry II and Arjay Miller, who had been promoted to president. The Deuce took a look at the thing and said, "It's a little tight in the back seat. Add another inch for legroom." In the end, Henry II told Iacocca, "I'm going to approve the goddamn thing to get rid of you. But once I approve it, you got to sell it. It's your ass if you don't."

By 1963, the buzz in the company hallways was palpable. In the long months of the Mustang's genesis, it began to appear more clear that the American market—and even Europe—was clamoring for something new. GM's young star executive, John DeLorean, had his Pontiac GTO in the pipeline. Chrysler was working on the Plymouth Barracuda. The clock was ticking, and it was still anyone's game.

By now, the Fairlane Committee had a launch date for the new Ford and a goal for its sales numbers. The car would be unveiled at the New York World's Fair on April 17, 1964, an opportunity that provided huge exposure, and because it would be a midyear model (a "1964 ½"), it would have less competition for the spotlight. As for sales, Iacocca aimed to break McNamara's first-year 417,000-unit Falcon record. Focusing on the launch date, the Fairlane Committee's mantra became "417 by 4/17."

Iacocca turned to J. Walter Thompson for help with the name. The agency sent an executive to the public library to hunt for ideas. Among those on his list: Cheetah, Cougar, Monaco, Bronco. The name chosen was Torino, because it sounded exotic and Italian. Then Iacocca got a call from a guy in Ford PR.

"You'll have to pick another name for your car," the man said.

It turned out that Henry II was secretly in love with an Italian woman and about to leave his wife for her. Company executives in the know didn't want people to think Henry II had named the model for his Italian paramour. Henry II and Iacocca settled on the name Mustang—not for a horse, nor for the two Mustang concept cars the company had previously unveiled, but for the World War II P-51 Mustang fighter. As the ad agency put it, the name "had the excitement of wide-open spaces and was American as all hell."

When it came to advertising this new product, who could compete with Iacocca, the Detroit auto man whose marketing prowess was compared with that of P. T. Barnum? The blitz—on a scale never before seen—began early in 1964, weeks before the car was unveiled, with a massive newspaper ad buy. Because the car was planned to appeal to different types of customers, ads were placed in men's and women's magazines. Radio commercials bombarded drivers across the nation. The campaign was genius. Ford was not selling a car, but an aspirational way of life.

"It was an almost Walter Mitty-like thing," recalls auto historian and museum curator Ken Gross, who had just graduated from college at the time. "It was like: If you have a Mustang, you will be immensely popular. You will get the girl ... And the affordable base price—$2368—was a major part of the ads."

Meanwhile, in a plot that showed his unmitigated audacity, Iacocca lied to the editors of both Time and Newsweek (extremely influential at the time), tricking them into running simultaneous "exclusive" cover stories on the Mustang. Iacocca appeared on the covers of both. (Time: "rhymes with try-a-coke-ah"; Newsweek: "pronounced eye-uh-coke-uh.")

The first Mustang, a Wimbledon White convertible that today sits in the Henry Ford Museum, came off the assembly line at Ford's Rouge plant in Dearborn on March 9, 1964. The plan was to build enough cars so that every dealership had at least one on the launch date. Just before the World's Fair, the company enjoyed a stroke of luck, an uptick in the stock market and the announcement of tax breaks by President Lyndon Johnson, which meant more cash in people's pockets.

Which brings us back to Gail Wise, who walked into a Ford dealership in Chicago two days before the Mustang launch and bought the first one, on April 15. The next night, at 9:30 pm, the company ran infomercials simultaneously on all three major TV networks, something that had never been done before. The move unveiled the car in front of 29 million viewers. The following day, Iacocca and Henry II debuted the car at the World's Fair in their "Ford Rotunda," seven acres of Ford cars and exhibits. In his address to the media, Iacocca began, "Good morning, ladies and gentlemen. Welcome to one of the proudest moments of our lives." At the same time, the car was launched in 11 European cities to thousands of reporters and photographers. No one had done that before, either.

The push continued. After the introduction, Ford gave 62 Mustangs to reporters, along with directions for a 750-mile rally route from New York to Dearborn. The car was splashed across billboards at busy intersections in more than 70 cities and 170 smaller markets. It was displayed in 15 airports and in the lobbies of more than 100 Holiday Inns.

The cheap sticker with the huge options menu proved a stroke of genius. Buyers averaged around $1000 in upgrades, or almost half the car's base price. Standard equipment included front bucket seats, a three-speed manual transmission, and a 170-cubic-inch inline-six rated at 101 hp. Other engine options included a 164-hp 260 V8 ($75.00 extra), a 210-hp 289 ($162.00), a high-performance 289 package ($442.60), a four-speed manual ($115.90 with the six, $75.80 with the V8), a Rally-Pac with clock/tachometer ($70.80), plus an array of tire, wheel, and accessory packages. Four out of five buyers ordered a radio ($58.50), 73 percent went for the V8, and half opted for the stick over the Cruise-O-Matic automatic.

The Mustang sold 418,812 examples its first 12 months, breaking McNamara's record. By March of 1966, the millionth car rolled off the line. "It was as if the Mustang designers tapped into the American psyche," wrote historian Douglas Brinkley. Pontiac's GTO and Plymouth's Barracuda appeared the same year, but the Mustang stole the show. The fact that Chevrolet's Camaro didn't arrive until 1967 shows how far ahead Iacocca was in conquering this new market. More important, the car reestablished the identity of a critical American brand and changed how the car industry talked to people, trickling down to how cars are sold.

Today, people are still walking into showrooms and buying Mustangs, many with a raft of options. "Who would have guessed?" Iacocca says, looking back. "A half century is a long life for a Detroit car. The Mustang launched my career ... I still have fond memories of those fun and exciting years at Ford."

A.J. Baime is the author of seven books, including Go Like Hell: Ford, Ferrari, and Their Battle for Speed and Glory at Le Mans, and The Accidental President: Harry S. Truman and the Four Months that Changed the World. An R&T editor-at-large, he has driven cars on racetracks all over the U.S. and Europe, going back to 2007. He is proudly the R&T staff’s slowest track driver.