How a new bike messenger firm got its wheels turning in India

- Published

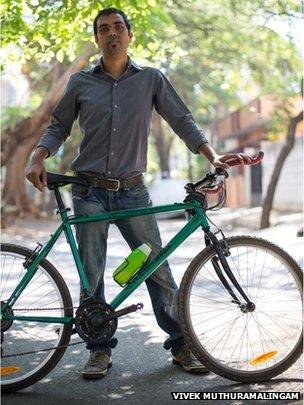

The idea struck Rajiv Singh during a business trip to Germany, when a man arrived with a document from an office on the other side of town.

At first Mr Singh, who is based in Bangalore in India, presumed that the delivery came from a postman - but he soon discovered that it was a bike messenger.

Also known as cycle couriers - this is a service well-established in many countries.

But as Mr Singh came across more and more of them during his stay in Germany, they became the inspiration for his business idea.

"I loved cycling and wondered why we couldn't have the same concept in India," he says.

And so he quit his job at a retail brokerage firm to start the operation.

When a friend got interested in the idea and agreed to invest in the start-up things really got moving.

And in December last year Banglalore-based Cyclercity became India's first bike messenger company.

Fortunately for Mr Singh, orders started coming in thick and fast from the day he opened the business.

With his cyclists now delivering up to 60 items a day, he expects to break even before the end of the company's first six months.

Funding barrier

But Mr Singh's venture is a rare story of a start-up taking off so quickly, smoothly and successfully in India.

Unlike most new entrepreneurs, he did not have to chase would-be backers and convince them to invest.

And with modest capital required, the funds from his friend and his own savings were enough.

"I just needed a small office space, a few bikes and some cyclists, so funding was never going to be a challenge," says Mr Singh.

But it is exactly that issue - money - which is a barrier to new businesses across the world - and India is no exception.

Despite being a big community of real potential, Indian start-ups find it difficult to raise initial funds.

For technology firms, the struggle is less pronounced. But for firms in most other sectors it can be hard.

"There is less risk appetite in this country. No-one is ready to make the first move," says Anshula Dubey, co-founder of Indian crowdfunding business Wishberry.

She argues that if an idea is too glamorous for conventional investors, backers in India typically wait for someone else to make the first investment before they take the plunge.

Others feel that because a new business can take months or years to really establish itself, that is also a deterrent.

"There is no paucity of funds in India, but very few start-ups are able come out with an IPO (Initial Public Offering) which would offer an exit route to early stage investors," says Mahesh Murthy, managing partner of Seedfund, a business that offers seed capital to start-ups in India.

This is exacerbated he argues, by India's lack of a junior stock market like London's Alternative Investment Market (AIM), which allows smaller companies to sell shares within a more flexible regulatory system - and offers investors more hope of selling their stake and getting a return.

Regulations nightmare

But is is not just about money. Bureaucracy and poor infrastructure are other major hurdles that first time entrepreneurs face in India.

Getting regulatory permissions is a major nightmare that many start-ups have to go through.

Sameer Hashmi reports on the challenges faced by India's young entrepreneurs

It's an environment that means the World Bank last year ranked India as the 179th country (out of 189 economies) for ease of starting a business.

But there are signs things are improving.

Anecdotal evidence suggests some investors are still willing to put cash into unproven concepts - helped by the launch of business incubation centres designed to support start-ups, and investment funds aimed specifically at backing new entrepreneurs.

And also helping produce more start-ups are market forces. The number of university and college graduates being offered large salaries has fallen sharply in the past five years.

That has meant more young people are willing to work for start-ups now than ever before, substantially improving the quality of people at these firms.

Cupcake pioneer

But for the likes of Shitija Nahata, it is still a struggle.

Her business concept - to open a shop selling cupcakes - would not be called adventurous in the US, the UK, Australia or Dubai. But in India it was still a new idea.

And so when she went to various banks that advertised special loan facilities for women entrepreneurs, she was turned down each time.

"I had seven years of work experience in reputed companies, I had all the documents in place but despite that they didn't give me a loan," says Ms Nahata.

Eventually she and her husband pooled savings and went it alone to open their first store, under the name The Cupcake Company. And it would seem investors who did not want to take a gamble may have missed out.

She now owns five stores across Bangalore and Chennai, and thinks others who want to start a business should give it a go.

Indeed the most common opinion across India's start-up community is that despite potential funding woes, there has never been a better time in the country to start a business.