Each Friday Roads & Kingdoms and Slate publish a new dispatch from around the globe. For more foreign correspondence mixed with food, war, travel, and photography, visit their online magazine or follow @roadskingdoms on Twitter.

GAZIANTEP, Turkey—Abu Yaseen won’t take no for an answer.

It’s a bright, brisk February afternoon in Gaziantep, a bustling city in southeast Turkey with a history reaching back to the Hittite empire, and a group of Free Syrian Army soldiers and I are scraping clean a bowl of a fatteh, a rich Damascene dish of chickpeas, yogurt, and tahini. The proprietor, surveying his canteen from behind the counter, quickly dispatches a second serving before we can ask.

“You like fatteh?” asks Yaseen, with a grin. The 65-year-old owner is from Aleppo, 60 miles south of Gaziantep in Syria. “Then you should eat more.”

The red sign over the entrance reads Orjinal Halep Lokantasi, and the business cards say Original Halabi Restaurant. (Aleppo is known as “Halab” in Arabic and “Halep” in Turkish.) But most customers call it Abu Yaseen’s. By any name, this modest eatery along a ripped-up side street has in recent months emerged as a place of refuge and renewal for Gaziantep’s fast-growing Syrian community—a little slice of their vanished, prewar homeland.

Courtesy of David Lepeska

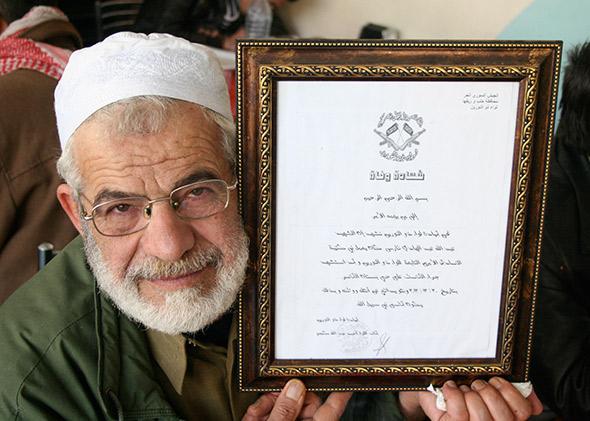

“It started as a small business, but it’s turned into a social message,” says Abu Yaseen, his kindly face framed by a bushy white beard and crisp white skullcap. “Everyone is coming here, thanks to Allah. Rebels, activists, journalists, all kinds of associations and ministries—the future leaders of Syria are here.”

Entering its fourth year, the war across the border churns on mercilessly, with the death toll crossing 150,000 and more than two-fifths of Syria’s population—nearly 9.5 million people—displaced, including 3 million who have fled abroad. The Turkish government in Ankara, staunchly opposed to Bashar al-Assad’s Syrian regime, has maintained open borders and spent more than $3 billion on refugees.

Some 220,000 of them have settled in camps on the Turkish side of the 820-kilometer (510-mile) border. Officially, Turkey has taken in 750,000 refugees, but a United Nations official recently put the total at more than 900,000 and rising. As many as 100,000 Syrians have crossed into Turkey since January when Assad began his campaign of barrel bombs—cheap, improvised explosives made from barrels stuffed with TNT and shrapnel that are pushed from helicopters—in Aleppo.

With the camps full, many make their way to Gaziantep, less than 30 miles north of the border. No Turkish city, and perhaps no city outside Syria, has been as altered by the war. Today, the city and surrounding area host at least 200,000 Syrians. Some local NGOs put the number at twice that—which would represent nearly a quarter of the province’s population.

Either way, their presence is unmistakable. Original Halabi Restaurant anchors an emerging “Little Aleppo” in the city center. Around the corner is a sleek new KFC-style chicken joint, with specials written only in Arabic script on the front windows. Nearby are two Syrian barbershops, Syrian-run mobile phone stores, a chocolatier, a café, and a juice bar. Syrian children beg on street corners, and groups of elderly and teenage Syrian men and boys crowd the sidewalks.

Many end up at Abu Yaseen’s—a bright, clean space with gray tiled floors, red tables, and picture windows looking out onto a stout stone minaret. Beneath a flat-screen TV tuned to Syrian opposition news, preteen waiters scurry back and forth with bowls of fatteh, plates bearing creamy hummus, crepe-thin omelets, and balls of falafel, and a steady stream of tea. The air is heavy with chickpeas, garlic, and olive oil, but the atmosphere is light, almost festive. The clientele is mostly young men, plus the occasional female activist or refugee family. On sunny days, they fill tables set up on a patch of dirt and concrete out front.

Abu Yaseen presides over the hubbub, shaking hands, joining in rebel chants, embracing the troubled, and, now and then, scowling at his staff. The wave of new arrivals has been good for business and a strain on local resources. As the lunch rush dies down, a few Syrian women in raggedy clothes totter out of the courtyard of the 17th-century mosque across the street, lugging pails of water.

They make their way to the abandoned stone house—no heat, no electricity, no roof—they recently occupied with their families. “We went to the camp,” says Umm Ali, two small children with runny noses standing beside her. “It looked great, but there was no space.” One local relief worker who has been helping Syrians find makeshift lodging—in basements, tents set up in driveways, even unused warehouses—says finding housing is the biggest problem for new arrivals.

With odd jobs scarce and little hope of obtaining a work visa, few Syrians have been able to make any real money. Meanwhile, housing prices in Gaziantep and other border cities have doubled or even tripled since 2011, according to local realtors. Partially for this reason, the fast-growing Syrian community has sparked local ire.

I witnessed no animosity between the two groups while in Gaziantep, and local Turks were generally accepting of the new arrivals. But some complained that the refugees slept in parks and apartment building lobbies; that their new businesses, from pharmacies to fast food restaurants, represented unwelcome competition; that police allowed them, likely as a gesture of hospitality, to commit petty crimes; and that by working for less money, the refugees had driven down pay rates. One academic I met in the city told me she saw locals throwing stones at a group of refugees to chase them out of their residential compound. Last month Gaziantep police found a Syrian dead with scar marks on his body and his mouth banded shut.

Courtesy of David Lepeska

Yet most Syrian refugees have seen far worse than hostile Turkish locals. And any fears seem distant at Abu Yaseen’s. Activists, drawn by the free Wi-Fi, sit for hours sipping tea behind laptops in a back corner. One regular is Amr al-Hamad of the Syria Media Action Revolution Team, a Gaziantep-based network of journalists and media activists.

Al-Hamad goes back and forth to Syria for his work. But he knows most Syrians are probably stuck in Turkey for years. That’s why Abu Yaseen’s is so important. “The food is good,” says al-Hamad, “and it reminds people of their own country.” You won’t find alcohol, but the little eatery may be the Syrian-refugee equivalent of Cheers. With hope all but extinguished back home, it’s more than a place to eat—it’s warm and familiar enough to prod Syrians to forget, even for a moment, their harsh reality.

Yakzan Shishakly, a Syrian-American who runs a refugee camp on the Syrian side of the border and spends a lot of time in Gaziantep, offers a simple explanation. “It’s just a normal restaurant—a place that maintains our culture,” says Shishakly, who grew up in Damascus and is a grandson of one of Syria’s first presidents. “People try not to think about the war or the future. And if we have the option to smile or not to smile, we have to smile to give other people hope.”

Zakaria Zakaria, a Syrian media activist and fixer living in nearby Sanliurfa, Turkey, tells me his war story—how he became a FSA spokesman for his hometown of Hasaki, Syria, because of his command of English, then watched its local chapter crumble—with a thin smile on his lips. “It’s sad, but we can do nothing to stop it,” he explains. “I’ve lost many friends and, I don’t like to say it, but we’re used to it. When someone dies, we say ‘Oh, God bless him. He was such a nice guy,’ then move on. The most difficult thing for me now is when I’m going through my contacts on my phone, seeing the names of friends I’ve lost, or on WhatsApp, seeing the last message sent by someone on the day of his death.”

Louay Muhammad laughs more than one might expect from a 23-year-old who has been shot three times and watched friends writhe in agony until they expired, whose mother has gone missing after she came to Aleppo to see her twin soldier sons. But his joviality is fleeting and skin deep. “It’s very sad to leave Syria even for a while,” he said. “It’s sad because my weapon is not pointed at the Bashar al-Assad regime right now. But we will go back to fight soon.”

Courtesy of David Lepeska

Abu Yaseen, beaming with pride discussing his customers’ appreciation of his food, tears up quickly when I ask about the death of his son. Fleeing Aleppo, Abu Yaseen arrived in Gaziantep with his wife and daughter in November 2012. His youngest son, Yaseen, arrived a few weeks later. The day before Abdulla, his middle son (his eldest son lives and works in Saudi Arabia), was to join them, he ran into trouble back in Aleppo. “Abdulla Abdulhadi Faris,” reads the FSA certificate hanging on the wall, “martyred due to shelling … while defending his people and his nation.”

Six months later, Abu Yaseen opened this restaurant to keep himself busy. It quickly became a way to honor his son’s legacy. To his right, near Abdulla’s martyrdom certificate, notices on a bulletin board offer work as a tailor, a driver, an electrician, along with medical services and apartments to rent. “Some people come here, they haven’t eaten for two days,” says Abu Yaseen. “We give food. We offer jobs. We help in every way we can.”

The conflict has wiped out a generation or two and laid waste to Syria’s economy, its proud cities, its health care and education systems, and its vast cultural heritage. Many expect the war to grind on for several years, scattering still more desperate Syrians. For the displaced, life will continue to be largely about making do in unfamiliar settings.

It seems fitting that this city—Antep, its original name, means “full of springs,” or “good spring,” while Gazi means “war hero”—should provide besieged Syrians a measure of renewal. “Our people are suffering from Bashar,” says Adnan Naimi, a dark-eyed 23-year-old FSA fighter, as he dips a hunk of bread into the fatteh. “But we will win because we are on the right side. We have fought for three years, but we are not tired. Even if we die, our younger brothers, they will finish it.”

Even if it’s only an escape, the laughter, smiles, and confidence of those who gather at Original Halabi represents a last line of defense, a necessary show of strength and defiance.